Recurrent Care Resource Pack: Section 2

Published:

This section considers setting up a service, evaluation and cost benefit.

Section 2: Setting up a service. Evaluation and cost benefit

This section covers:

- Why evaluation is important.

- Key issues to consider when planning an evaluation.

- Learning from recent evaluations.

- Developing a theory of change, identifying desired outcomes.

- Value for money, cost-effectiveness and cost-benefits.

Why evaluation is important: Key issues to consider

Slide Presentation: ‘Key points about evaluation’

Time: Allow 40 minutes for this overall (30 minutes for the presentation and 10 minutes for discussion)

What to do: Use the five slides and the accompanying notes. Encourage comment and discussion during the presentation. Keep a note of ideas and suggestions for your approach to evaluation.

Notes to accompany the 5 'Key points about evaluation' slides:

Slide 1: Evaluation provides a framework within which to do what is outlined on this slide.

- It helps you demonstrate that your service is making a difference.

- It gives you the ‘charismatic’ fact or facts about your service – the information from an evaluation that helps you sell your service, to commissioners, partner agencies, local politicians.

Slide 2: It’s important to think about evaluation at the earliest opportunity because it encourages you to think clearly about:

- What you are trying to achieve?

- How you are going to record what you are doing?

- How you are going measure whether or not you have been successful?

Change Project participants spoke from experience about the risks of not thinking about evaluation at an early stage, and then finding later on that they had not collected crucial data.

Slide 3: Time: Even when staff understand the importance of evaluation, it can sometimes be difficult to encourage them to collect the data you need and to input it onto your system. This means you’ll need to think about not overloading people with information to collect, making sure staff can readily combine data collection activity with their direct work, and having easy-to-manage data systems. Making sure data is being collected is a key task for team managers.

Capturing flexible approaches: It is important to record what work is done with each person, rather than just what might have been offered. This helps provide a picture of the range of activities with parents.

Data systems:

- You may need to develop one specifically for the service. You will be working primarily with adults, so children’s services IT systems may not be the best for collecting the data you will need.

- An interdisciplinary team at the University of Essex, working closely with service providers and specialists over several years, has developed an evaluation tool designed to support practice teams to assess the impact of their work. It has been used to complete evaluations for the following services: Positive Choices (Suffolk County Council), Mpower (Ormiston Families, East of England Region) and the Parent Infant Mental Health Attachment Project (Norfolk and Suffolk) Recurrent care evaluation tool user guide.

- Some services use data systems developed specifically for their project. For example, all FDAC teams use a specially designed database and Family Nurse Partnership teams feed their data into a centrally held system. The advantage here is that services using a particular model are collecting data in the same way, so the information from different services can be analysed together or compared.

- Analysing data is not a simple task. You should consider in advance whether you will need to employ someone with skills in data analysis, or whether you might be able to make use of external expertise from a local university, for example.

Managing expectations: It may take time some time to build up the numbers of parents you are working with and for outcomes to begin to emerge. Think about what early indicators you will use to demonstrate that you are on track to meet your outcomes, so you can keep senior managers and commissioners on board.

Slide 4: Both quantitative and qualitative data are needed for an evaluation. Think about ways in which you can capture feedback from parents and from other professionals. The voices and stories of parents using the service are always a very powerful way of getting the messages about the benefits of your service across.

Slide 5: Ideally, an evaluation will include some form of comparison. However, this can be hard to achieve if the evaluation is being done by service staff themselves and/or resources for the evaluation are limited.

- The best type of comparison study is a randomised control trial (RCT), which are frequently used in the area of health to test medicines and occasionally used within children’s social care interventions.

- Comparative evaluations are more commonly used in the field of children’s social care. These evaluations use a matched group of parents, with similar backgrounds and problems to those receiving the service that is being evaluated. The comparison group either receive no service (possibly because they’re on a waiting list) or a different service (commonly, ‘service as usual’).

Learning from recent evaluations

Slide Presentation: ‘Evaluating local services to reduce recurrent care’. Examples of two approaches to evaluation: (1) Positive Choices and (2) PIMHAP (Norfolk Parent Infant Mental Health Attachment Project)

Time: Allow 60 minutes (45 minutes for the presentation and 15 minutes for discussion)

This slide presentation - 'Evaluating local services' - has been compiled by Professor Pamela Cox and Dr Susan McPherson from the University of Essex. They offer an overview of their evaluations of two local services, one aiming to reduce recurrent care proceedings (Positive Choices run by Suffolk County Council) and another to improve edge-of-care family interventions (Parent Infant Mental Health Attachment Project, PIMHAP, run by Suffolk and Norfolk NHS Foundation Trust).

The slides describe the evaluation approach taken in each evaluation, the activities of the two services and outcomes achieved by both. Both evaluations combined qualitative interviews to capture the voices of parents and practitioners, and quantitative measures to capture changes in parents’ self-esteem and decision-making, using validated, clinically reliable tools. The researchers have now designed a tool to support evaluation based on their experiences of carrying out these evaluations. Access the Essex evaluation tool and a guide on how to use it.

Key learning from the ‘Evaluating local services’ presentation

Learning gained from the Positive Choices and PIMHAP evaluations suggest the following factors should be considered by those developing services in these fields:

- The quality of relationships is key – this means trust, reliability, and confidence.

- Practitioners support clients, and managers support practitioners.

- The service knows the local client profile and local assets and challenges.

- The service is tailored to clients: there are no predetermined goals.

- The service makes sensitive use of prior information: court report, social work reports.

- The service integrates social care, mental health and other services.

- Contraception is not required, but is encouraged.

- Evaluation is built into the service: baseline outcomes and experiences of clients and practitioners. Evaluation takes a long view wherever possible.

The evaluations indicate how services like these can generate substantial savings through ‘avoided costs’. For example, the evaluation suggests that the work of the Positive Choices team is likely to have led to the avoidance of nine repeat pregnancies among their engaging mothers which would likely have led to nine sets of removal proceedings. Given that a single set of proceedings can cost at least £50,000, Positive Choices activity generated potential savings on care proceedings alone of £450,000 in a single year.

Findings like these can be thought of as ‘charismatic facts’ – a term used by social scientists to refer to the power carried by certain facts or findings. For example, in a commissioning setting, clear evidence of the avoided costs generated by a service carries particular influencing power. The same is true for clear evidence of the emotional benefits of that service for parents and practitioners.

Overall, sound evaluation is essential to sound service design and delivery in the recurrent care field.

Learning from published evaluations

Reading published evaluations of similar services is helpful. An evaluation will indicate what outcomes a service was aiming to achieve and explain how these were measured, as well as describing any problems that arose. Increasingly, evaluations look at issues of cost, cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit, so evaluations can also provide examples of how cost savings have been identified.

Here are some links to published evaluations that you may find helpful:

- Cox et al (2015) Reducing recurrent care proceedings: Service evaluation of Positive Choices (Suffolk County Council) and Mpower (Ormiston Families). University of Essex.

- McCracken K et al (2017) Evaluation of Pause: Research report. Opcit Research and University of Central Lancashire.

- Bellew R and Peeran U (2017) After Adoption’s Breaking the Cycle programme: An evaluation of the two year pilot, September 2014 to August 2016. Coram.

Identifying desired outcomes and developing a theory of change

Slide Presentation: ‘Outcomes and how to measure them’

This slide presentation, and Exercise 5 which follows, provide an opportunity to think about the outcomes you aim to achieve by developing your service, and the ways in which you can demonstrate that these desired outcomes have been achieved.

Time: Allow 15 minutes for the presentation (and another 30 minutes for Exercise 5)

Notes to accompany slides:

Slide 2 (NB: Slide 1 is the title slide)

- Despite all the focus in recent years, there can still be some confusion around identifying outcomes.

- Outputs are the products of your service or intervention – for example, the number of parents worked with, the training delivered, the information produced.

- Outcomes are about the impact of your service – most commonly, the change that has been achieved by the individuals receiving a service or intervention.

- With services set up to address recurrent care, you are likely to be looking to achieve an impact not only on the parents, but also on their current and future children and on local services. So it can be helpful to think about outcomes under the headings of ‘impact on individuals’ and ‘organisational impact.’

- When thinking about outcomes for services, it will be important to think about outcomes that are relevant to key partners – for example, in health and adult social care, and not just Children’s Services.

Examples of potential outcomes:

- Outcome for parents – parents are less isolated, have a supportive social network, are making informed choices about contraception.

- Outcomes for Children’s Services – there is a reduced level of recurrent proceedings leading to the removal of children.

- Outcomes across services – improved co-ordination of pre-birth support and assessment, better understanding among staff of the impact of complex trauma on parental behaviour and how to respond to that.

Slide 3

- When identifying outcomes that are about individuals achieving change, think about what your assumptions, or the evidence, tells you is realistic to aim for. For example, do you think 30 (or 50 or 70) per cent of the mothers you work with will be able to avoid coming back into proceedings for the period of time you are working with them?

- You might be thinking of setting up a service that follows a particular model, for example FDAC or Pause. If so, arguably you should expect the same outcomes as those achieved in the evaluated pilot. For example, the FDAC evaluation found that 37 per cent of mothers in the pilot FDAC were reunited with their children at the end of proceedings (compared with 25 per cent of comparison mothers). So a newly established FDAC, with fidelity to the model and with a similar caseload, would be aiming for the same level of success.

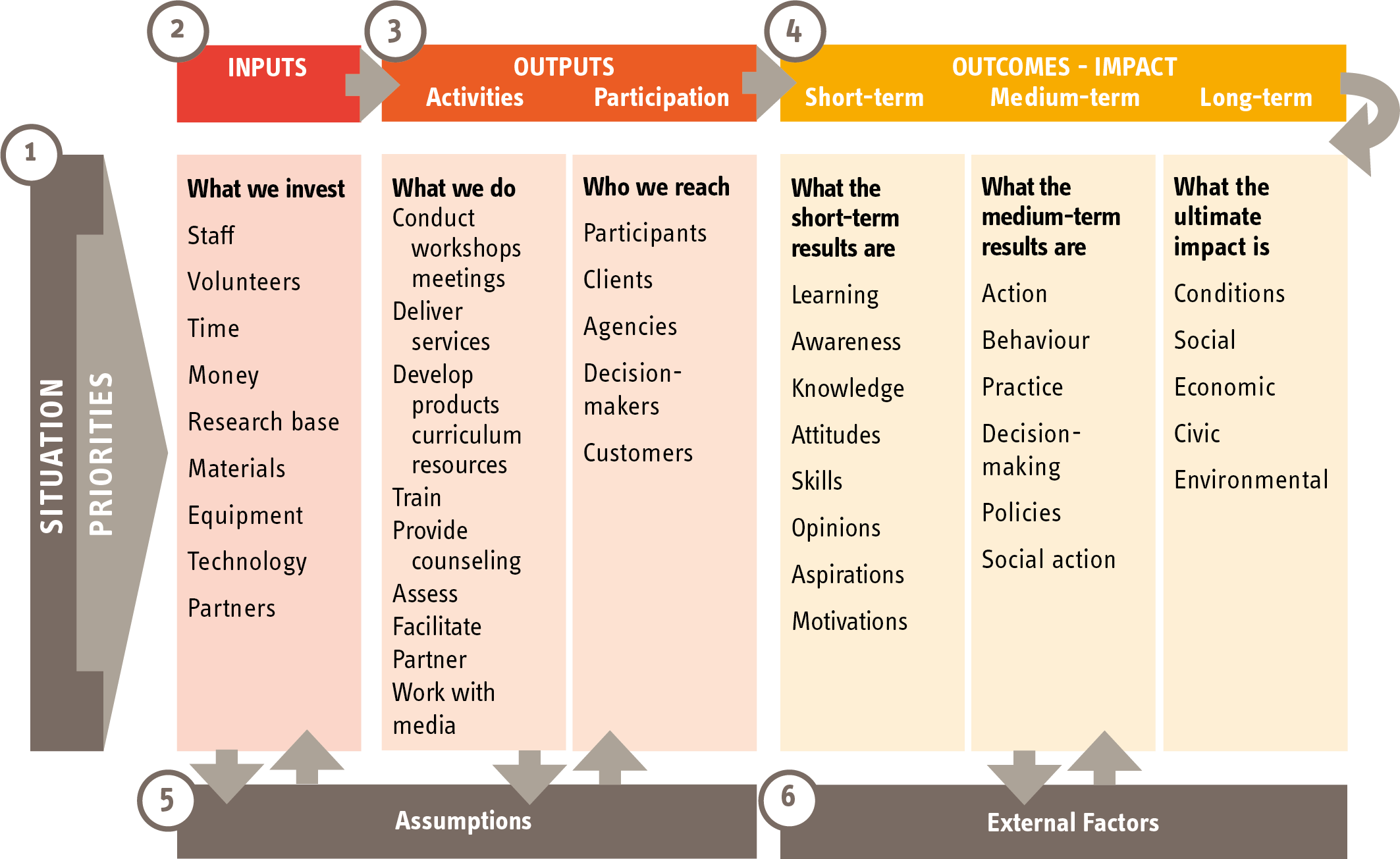

- Developing a ‘theory of change’ or ‘logic model’ (see diagram) is one way to help plan an intervention around outcomes you are aiming to achieve. They both contain the same basic principles: Inputs (budget/staff) – outputs (activities, products) – outcomes – overall aim, underpinned by enablers (internal and external context) and underlying evidence or assumptions (underlying beliefs about how an intervention will work)

The logic model diagram

Here are links to some documents that you may find helpful:

- An example of the use of the logic model from an organisation called Evaluation Support in Scotland.

- A 2014 guide (from New Philanthropy Capital) to developing a theory of change.

- Examples of a theory of change developed during the period of the Change Project by representatives from Leeds.

- A logic model developed for local FDAC teams.

Slide 4

- You will probably use a range of ways to measure outcomes.

- Comparing information collected at the start of your contact with parents, and at the end: this will include factual information, and also the views and opinions of the parents themselves and the professionals working with them. Where you are relying on professional opinion and self-reporting to measure outcomes, it is always helpful to have more than one opinion on an issue.

- There are a growing number of standardised measures available and their use may be relevant to the work you are doing. Standardised measures have been tested in a variety of settings to establish their reliability. If standardised measures are used, they will usually need to be used at the start and at the end of your involvement with parents, in order to provide a ‘before’ and ‘after’ perspective. It is helpful to find standardised measures that can be incorporated into the work you are doing with parents. The slides on evaluation by Essex University and their evaluation tool list some commonly used standardised measures.

- The Outcome Star is a method that has been devised to give central importance to the user perspective.

You can look at examples of how other services are measuring outcomes with the FDAC outcomes framework and Leeds futures outcomes framework.

Slide 5

- Probably the greatest challenge for a small team or organisation is finding the time to collect the data you will need to demonstrate outcomes. The risk of not finding the time, however, is that you lack the information to demonstrate the effectiveness of the service and to argue for continued funding.

- Another challenge arises from services that do not carry out detailed assessments at the start of contact, or those where parents are encouraged to drop in and out as they wish. Brighton and Hove’s Looking Forward service dealt with this issue by developing five levels of service, from being notified of a potential client through to a defined intervention, as can be seen on page 6 of their 2017 Annual Report.

- If you are considering using standardised tools it is always worth checking what they might cost, and how user friendly they are.

- Sometimes change can be hard to measure. During the Change Project participants talked about the important small changes that parents might demonstrate over time, such as taking their hoody off when talking to a professional, or not swearing at the professional when discussing things with them or being able to manage their repeat prescriptions.

Exercise 5: Outcomes and how they might be measured

Time: Allow 30 minutes for this exercise

What you’ll need: Flipchart paper and marker pens or Post-its.

What to do: After watching the slide presentation ‘Outcomes and how to measure them’, work in pairs or in small groups and record suggested outcomes on flipcharts or Post-its.

You can use the prompts set out below to stimulate your discussions. Keep a record of the suggestions for future reference.

Outcomes: Prompts for discussion

Participants in the Change Project identified a wide range of potential outcomes for parents, children and organisations. Some examples are given below. You can use these as prompts for your discussions in Exercise 5.

Parents

- have developed insight into how their past has impacted on their parenting

- are more in control of their life

- have developed the ability to make better choices

- are better at managing contact with their children who have been removed

- have developed supportive friendship networks

- have improved relationships with their families

- are making appropriate use of support services

- are not in oppressive relationships

- are making informed choices about contraception

- have improved physical health and wellbeing

- are in education, employment or training

- have improved mental health

Children

- have improved mental health

- are having improved contact with their parents

- are not born substance dependent

- are not removed/moved at a very early age

- are meeting their developmental milestones

- are able to stay or return home to live with their parent or parents

Organisational outcomes

- A reduction in the number of women/parents coming back into proceedings, particularly with unborn children.

- A reduction in the level of recurrent removals in the area.

- Financial savings for the local authority.

- Improved understanding about the impact of trauma among relevant services and staff.

- Fast-track systems into services for vulnerable parents.

- A reduction in the barriers to accessing services.

Value for money, cost-effectiveness and cost benefits

The issue of costs will arise when you are first making the case either to set up or further develop a service, and it will continue to be an issue for senior managers and commissioners, so it is important to understand how best to make your business case.

However, as the Change Project participants emphasised, while costs are important, so are values. A system that focuses on removing children, without tackling the reasons underlying the need for removal, is a system that is not functioning as it should. Safeguarding children does not mean that we cannot show understanding, humanity and empathy for their parents.

Exercise 6: Costs, cost effectiveness and cost benefits

Time: Allow 30 minutes for discussion

What to do: Using the slide as a visual prompt for structuring a discussion about costs, go through each of the points below. Record the group’s suggestions to inform your service planning.

Costs – top-down or unit costs

Commonly, the costs of a service will be identified through the budget needed to pay for salaries and oncosts, plus costs for overheads. This may then be divided by the number of people the service works with, to give an average cost per case. This is called ‘top-down’ costs.

A more complex, and more accurate, way of identifying costs is by tracking the activity of all staff over a period of time, usually a week, taking account of the salaries and overheads of each staff member. If necessary, this exercise can be done per case. This is called ‘bottom-up’ costs. It will usually indicate that some cases cost more than others, or that activity is concentrated at particular points of intervention. It is still unusual for this method to be used in Children’s Services.

Cost-effectiveness

Identifying whether a service is cost-effective depends on knowing how much the service costs, and whether it is achieving its intended outcomes. A service is cost-effective if it is cheaper than another service achieving the same outcomes, or more expensive than another service but achieving better outcomes. In order to establish cost-effectiveness, you will need to compare the service to something else (although that could be ‘services as usual’).

Cost benefit

Cost benefits are the longer-term cost savings and associated personal, social and economic benefits accrued from the outcomes your service achieves. In order to establish cost benefits, you need to be able to demonstrate what outcomes you are achieving, which obviously means you cannot describe cost benefits before you start your service. However, if you are following a particular model that has already been evaluated, you can base your arguments on the outcomes shown to have been achieved by that model previously, or you can make assumptions about what you hope you’re going to achieve. So, for example, you might argue that if your service helped avoid three removals of children through care proceedings, then that might cover the cost of the service.

Cost benefits include, but are not limited to, cashable savings, or avoided costs, for the commissioner of the service – in recurrent care services, that is usually the local authority or health trust or clinical commissioning group. A challenge for sustaining a service in the current climate is the pressure on local authorities to show cost benefits in a short period of time. Cost benefits are usually considered over a two to five-year period, rather than over the space of one year, and will take account of savings that may accrue to a wide range of services. This can be helpful when seeking funding from different partners, but also problematic if the main funder does not see sufficient benefit for their service.

Making the cost-benefit argument for recurrent care services will involve looking at things like a reduction in the use of foster/residential/secure care or mother and baby homes; reduction in social work time; less use in the longer term of physical health services; less involvement in crime; less use of substance misuse services or mental health services; and less use of court (Cafcass, judges, lawyers, experts).

Making the cost benefit/value for money case means finding out how much such things as mother and baby foster placements, or bringing care proceedings, cost. Sources of information include:

- Evaluations of similar services.

- Business cases prepared for other services – see, for example, the FDAC business case.

- The Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) which has branches at the London School of Economics and the Universities of Kent and Manchester.

- Local authority legal teams for legal costs (and the cost of expert reports)

- Public Health England for costs of treatment services and cost of crime connected with substance misuse.

- Research in Practice has many helpful resources on planning evaluations, see Evaluations and primary research.

Exercise 7: Review your service model

Time: Allow 25 minutes for this exercise

What you’ll need: The template you completed at 1.5 Designing Your Service and you can also make use of the logic model outline.

What to do: Go back to the service model you have begun to develop.

Think about how you might develop a theory of change or logic model and use the information you have already pulled together to describe:

- Inputs and resources (staff/budget).

- Activities and outputs.

- Your intended outcomes.

- Potential cost benefits. At this point you can just identify the areas where you would expect cost benefits to accrue.

Think about and discuss data collection for evaluation, methods, and resources and capacity to capture key information.

Key points from this section

- Ensure that data is collected regularly, that it is good quality and paints a clear picture of your activities, outputs and outcomes.

- Find the time to give presentations to frontline teams and to senior managers to keep knowledge and interest in your service alive.

- Keep an eye on communication and wider publicity throughout.

- Keep proving the benefits.

- Any form of evaluation, however light touch, needs to have time and resources allocated to it from the start.

- Information sharing with partners – have systems set up from start.