Communication and confidence

What this means

This is a big topic, and ranges from people who do not communicate verbally and assumptions being made about how they wish to live their lives, to confidence in navigating the health and social care systems.

If getting what you are entitled to depends on communicating in one particular way (such as over the phone or via the internet), or is dependent on knowledge of jargon or legal processes, that system is not equitable and not accessible. Time, a range of communication methods, and patience, are all key in addressing this.

The difficulty is that services often do not allow people time to communicate in the way that they need to.

The research

Just as in the sections in the Sharing Power As Equals key change (Power can be subtle and unspoken and Simplify!), and Living In The Place We Call Home (The importance of accurate and reliable information), communication – and organisations paying attention to the importance of this - was deemed vital by the Leading The Lives We Want To Live group.

To illustrate how fundamental individual confidence and the ability to self-advocate (or to have someone to advocate on your behalf) has become to navigating social care, it’s helpful to look at access to personal budgets and direct payments in social care. Hyslop et al. (2020) identified a ‘sympathetic cultural space’ as being important for the take-up of personal budgets among people who were entitled to them, which could include both professional and peer support, plus belief in concepts such as the social model of disability and the right to independent living. Confidence and assisted communication are consistent themes across the literature on the take-up and successful use of personal budgets (Hyslop et al., 2020).

Minic and Smith (2022) looked at the Scottish context of self-directed support (a system enshrined in law in Scotland, where people have a legal right to choose from four options for their social care, including to take direct payments). Among the findings were:

- People often needed more than one conversation to work out the best approach for their support.

- There was value in broadening conversations to family members and other professionals, to gain different perspectives.

- While the option of direct payments was considered the avenue for greatest choice and control, people felt underinformed about the bureaucracy and responsibilities involved.

- Information was not always provided in a range of languages.

- ‘Local authorities’ overly prescriptive and inflexible approach to how self-directed support can be used was a common experience’ (p.40).

(Minic & Smith, 2022)

Underpinning both of these pieces of research are two related ideas. The first is that access to self-directed support, and the choice and control it offered, needed clear and empowering communication. The second is that this clear and empowering communication, in itself, needed time, space, and accessibility to happen.

What you can do

If you are in direct practice: The fundamental point made by the Leading The Lives We Want To live group (related to the theme on empathy and kindness) is that, if there is time for worker and person to get to know each other, they will be more likely to understand each other. This means that workers will truly understand what is important to people, why people want the things they do, and how their wellbeing will improve if they are able to do them.

While the group realised that being in frontline practice could be complex and stressful, they urged a rethink in how time was apportioned. For example, if people did not understand something, they were more likely to either give up on it (and thus risk their needs worsening, or independence being compromised), or contact the worker again for help, thereby using up more of everyone’s time.

While there isn’t a magic bullet to achieving more time in a social care world of constricted resources, you may reflect here on the support you provide for communication and understanding.

- Do you know where people can access advocacy, and do you regularly share this?

- Can you follow up complex conversations with people, to check their understanding and ask if they need any additional help?

- Are you clear in your own legal literacy and confident you can support people to ensure their rights are upheld?

- Do you feel comfortable raising issues of time management in your team?

If the answer to one or more of these is ‘no’, think about raising these issues with your supervisor, working together to explore how you can develop these capabilities in your practice.

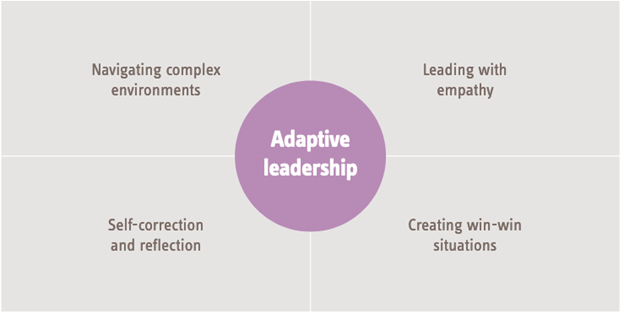

If you are a supervisor: In the role of supervisor, you have moved ‘from the dancefloor to the balcony’. This means that you can practice ‘adaptive leadership’, which is a way of working which can be particularly effective where there are no easy solutions. There are four dimensions adaptive leaders keep in mind:

(Shaw, 2019)

You can use this model when thinking about the difficult question posed by this theme - how can you foster more supportive communication, which requires time and space, in a sector which is often short of both of these? For instance:

Navigating complex environments

How can you support your supervisees to reflect on this challenge, and plan for the future? For example, consider the tension between the short-term need for work to be completed, with the longer-term goal of improved wellbeing. Who else might need to be involved in these conversations?

Leading with empathy

How does the lack of time to spend with people affect your supervisees? And how do your supervisees think the lack of time affects people with care and support needs?

Self-correction and reflection

What can be tried to change this situation? Try to accept that your approaches to address this might fail – and be willing to make changes and corrections. How can you obtain meaningful feedback on any new approach from people with care and support needs, and then act on it?

Creating win-win situations

Try to move away from a zero-sum approach (that if you allocate more time in one direction, something else must inevitably suffer). What would success look like for everyone in this situation? What steps can you take to achieve it?

Further information

Watch

Skills for Care has a webinar on practical time management in social care.

Read

Research in Practice has a practice guide on Supporting practitioner wellbeing.