Connecting the short and long-term

What this means

There can be tension between what is effective in the long-term – supporting preventative work and providing true foundations for a better life – and necessary short-term actions to tackle crises, which tend to be expensive and reactive. When time is taken up with the short-term, the long-term work is crowded out, leading to the higher likelihood of crises in the future (and higher expenditure).

Thinking positively, it’s also about smarter work to join up the short and long-term – translating the actions that happen on a smaller-scale to larger, longer-term action. People are not greedy, and they will know what needs to be there to prevent needs worsening and/or improving quality of life – it’s about harnessing this information for better long-term outcomes and, at the same time, reducing the need for short-term crisis management.

Millions of small steps, collectively, put us in a better position.

How can preventative work support better use of resources?

In these videos, Susan Bruce and Laura Collins talk about how preventative work can support better use of resources:

The research

The Care Act’s focus on prevention has been found to have only been partially successfully implemented (Burn & Needham, 2021). The study found that ‘Given the resource-constrained environment, local authorities were finding it difficult to sustain investment in prevention. A national policy emphasis on addressing delayed transfers of care from NHS services encouraged a focus on providing traditional social care placements rather than exploring preventative alternatives. Reductions in staff headcount had limited the ability of local authorities to embed the cultural changes required for a preventative approach’ (Burn & Needham, 2021, p.4).

SCIE (2021) found that the evidence for prevention leading to cost-efficiency in social care is ‘underdeveloped’. This is partly because there can be different understandings of what prevention is (is it the prevention of need for services, or is it prevention of barriers emerging to someone’s outcomes?). The research has also found difficulties in demonstrating the link between specific preventative interventions and outcomes. There are also, often, long timeframes involved for observing the full consequences of preventative investments (SCIE, 2021).

However, the More Resources, Better Used group offered suggestions to connect up the short and long-term. Particularly considered was the importance of Kaizen – the Japanese art of continuous improvement. This is an approach that involves daily improvement actions for everyone in an organisation, at every level from senior leaders to administrative staff, based on the idea that small, ongoing positive changes can yield significant larger change over the longer term – therefore combining the short and long-term. A cornerstone of Kaizen is ‘…the people who work in the organisation and all that is human about their presence’ (Pasmore, 1988, p.25).

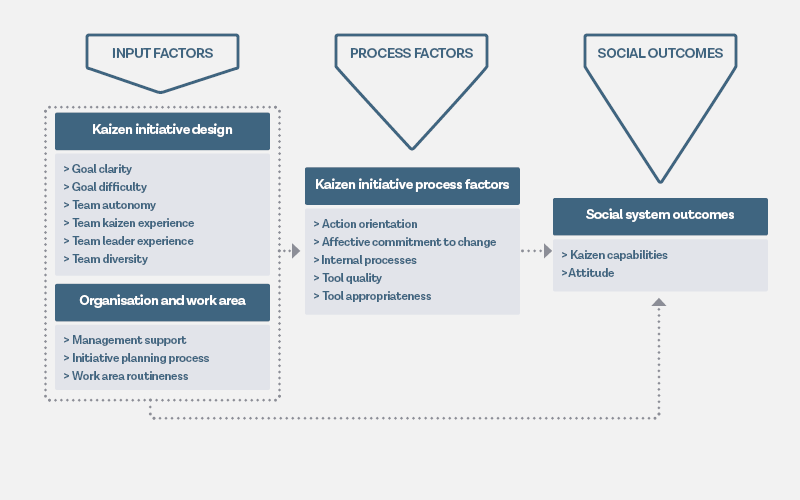

A framework for Kaizen was developed by Farris et al. (2009), and looked at which input factors are necessary for, firstly, improvements to process, and, secondly, improvements to outcomes (see below):

Adapted from Farris et al. (2009)

So, for example, people being clear on what Kaizen is and what it aims to achieve (goal clarity), would contribute to people adopting it in their work (action orientation and affective commitment to change) and, then, becoming more skilled in a Kaizen approach (Kaizen capabilities).

Bortolotti et al. (2018) studied the use of Kaizen in healthcare settings. They found the following:

- Goal clarity was highly important to making Kaizen work in healthcare. It is particularly important when healthcare works alongside other professions, because it can help with overcoming differences in professional approach. It also reduces staff anxiety that Kaizen will compromise patient outcomes.

- Team autonomy, not on what Kaizen is but how it is achieved, was also found to be important. Trusting that teams can identify their own continuous improvement actions, rather than insisting on a standardised process improvement cycle encouraged ‘professionals to be innovative and practice their activities as an art as well as a science’ (p569).

- Management support – including the allocation of resources – enhances staff motivation to participate actively and enthusiastically in Kaizen initiatives.

- The role of goal difficulty was complex. While goals shouldn’t feel unachievable and therefore result in frustration, staff did need to feel that their capabilities were being stretched and developed.

- Finally, affective commitment to change needed to be cultivated. This was the strong belief that Kaizen would deliver benefits for patients, and help practitioners address many of the issues they see in their working life.

This aligns with much research about what helps change happen in social care; for instance, Miller and Freeman (2015), when looking at change in social care, found the following important:

- Agreeing underlying principles.

- A lead from senior management.

- Co-producing the outcomes for change with people with care and support needs.

- Fostering trust.

- Choosing an approach with buy-in from all who need to implement the change.

- Ensuring staff have sufficient capacity and resilience.

Other suggestions from the group to support improved joining up on short and long-term outcomes included the work of The Q Community, the THIS.Institute and the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

As with all improvement in social care, what is improved and ensuring those improvements benefit those with care and support needs, can most effectively be achieved through co-production (Sutton, 2020). This would involve asking people about both short and long-term improvements they wish to see, and co-producing the journey with them.

What you can do

If you are a senior manager: Assessment was an area the More Resources, Better Used group thought was a prime example of how the short and long-term are linked. Improvements to the assessment process could really help the accuracy and effectiveness of assessments, and support better and earlier care planning, which could then help prevent or delay needs worsening.

Thinking along the Kaizen principle of small, daily improvements, what are some of the small, daily improvements that could be made to adult social care assessment in your organisation? You might think about:

- What people with care and support needs think could be improved about the process, and their ideas for doing this.

- What practitioners who carry out the assessment process think could be improved, and their ideas for doing this.

- Any frustrations and blockages you’ve noticed in the process, for instance with computer systems, forms, or layers of oversight.

- Any gradual improvements that can be made to key practitioner assessment skills, such as analysis, note-taking, preparation, being strengths-based (the Research in Practice handbook on Good assessment can help practitioners identify and work on these).

The Kaizen approach can be used with numerous aspects of adult social care. What are the key things in your organisation that might benefit from small, continuous improvement?

Further information

Watch and learn

SCIE has a learning resource on organisational change in social care.

Read

SCIE has a resource on prevention in social care.