There are a number of barriers to effective safeguarding during transitions from youth justice to probation.

A new scoping study, published by His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation, explores Transitional Safeguarding in youth justice and probation services.

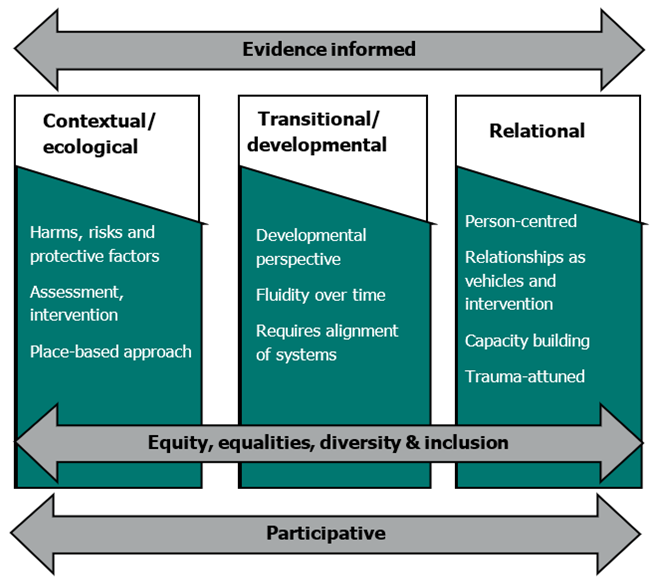

Colleagues from the School of Social Work at the University of East Anglia and Research in Practice have spent the past year investigating how youth justice services and probation services work together in their transitions and safeguarding work with young people aged from mid-teens to mid-twenties. We wanted to know about the support given to young people during the process of transitioning between the two systems. This inlcluded how youth justice and probation embed the six key principles of Transitional Safeguarding into their practice and service design.

The key principles of Transitional Safeguarding

Transitions between services

This is a complex issue as most young people using youth justice services do not transition between services at 18. They see out their sentence in youth justice services. If they reoffend as adults, they move immediately into probation, most often with no handover and little or no information sharing between probation and youth justice workers.

We used a literature review, survey, secondary analysis of data from His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation, interviews and focus groups as methods in the research. The survey and secondary data analysis encompassed all of England, whilst the interviews and focus groups focused on five study sites.

Our study found that there is impetus for a Transitional Safeguarding approach at practice and strategic levels. However, translation of this into direct practice has either not been fully evidenced currently or is not often happening. Leaders and practitioners in youth justice and probation recognise the need for transitional arrangements to be different than they are now. The social policy framework exists, but the practice and system realities impact on how transitional support is offered to young people. Participants told us that practice needs to be less reliant on rigid structures and offer more flexibility to work in a personalised way with young people. This is difficult to achieve with the current pressures on probation colleagues.

Differences between probation and youth justice

Practitioners we spoke with were reflective about the differences between probation and youth justice. There were comments about youth justice being ‘overprotective’ from both probation and youth justice practitioners. Some responses suggest that some young people lack boundaries and necessary life skills for transition into adulthood and that this should be redressed. Some practitioners - in both probation and youth justice - describe the probation system as ‘too harsh’, focusing on public protection as is necessary but sometimes without adequately considering the individual needs of young people.

There are issues with the language used by youth justice and probation when talking with and about young people. Binaries in language were noted - for example, boy/man; child/adult - that emphasise the cut-off point between services rather than the young person’s stage of development.

In terms of transitional approaches and arrangements, youth justice responses in the survey showed they were better able to meet the six principles than probation, particularly transitional, relational and participation. There are several reasons for this, including a culture in probation where the balance between public protection and rehabilitation is often distorted by resourcing, with practitioners ending up spending their available time on short-term public protection checks.

No routine data is collected on transitions between services. ‘Transition’ is not mentioned in case-level inspection data of individual settings or other data points identified for movement between services. The focus of safeguarding in the adult data (routine inspections) is not about the specific circumstances and safeguarding needs of the adult on probation, but rather, mentions of safeguarding emphasise community protection and risk to others, specifically children associated with the adult on probation.

Young people with experience of probation services

We also spoke with a number of young people who had experience of probation services. They shared with us their frustrations:

The current system doesn’t work because it is based on punishment and is setting us up to fail.

Young person with lived experience of probation services

Young people spoke about the importance of a personalised approach:

You need to ask the person what works for them and what like, how can we support you like you need.

Young person with lived experience of probation services

Equity and diversity issues

There are several equity and diversity issues to take forward too. Most young people subject to youth justice and probation service supervision are male. This raises issues for service development for young females as a minority group, particularly as they have a different offence profile. The differences in data for ethnicity between youth justice and probation requires further investigation in terms of the impact it may have on how services are developed for racially minoritised individuals.

Neurodiversity and speech and language difficulties (including pre-diagnosis) are cited as common themes related to equity, diversity and inclusion, along with mental health difficulties, care experience, sex and gender, sexual orientation and race/ethnicity. Regional (for example, Southern versus Northern English) and rural-urban differences affect available support infrastructures, particularly for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ+) or Black and Global Majority young people. The wider literature notes concerns about systemic adultification affecting these young people in the youth and criminal justice systems.

Given current pressures on the probation system nationally, it can feel as though there are limited opportunities to innovate. There were also issues about how much change could occur locally in specific probation sites, involving existing partners, or whether probation needed to wait for national guidance/published protocols to introduce changes to working practices with young people.

We have met some fantastic people during this work who are thoughtful and dedicated to supporting young people. Staff from both youth justice and probation working at all levels within these organisations expressed their frustrations with systems, structures and processes they had to work with that did not meet the needs of young people. There was a clear wish to ‘do the right thing’ for young people that would make a difference to the risks and harms they experienced in their lives. Given the complexity of problems that these young people were facing, the solutions were not straightforward.