Working effectively to address child sexual exploitation: Evidence Scope (2017)

Acknowledgements

Research in Practice would like to extend heartfelt thanks to Jan Webb, Principal Lecturer and Professional Lead Child Health and Welfare at Greenwich University and lead author of the original version of this scope. Her hard work and that of Charlotte Oram, Research Assistant, over many months is much appreciated.

We are thankful to busy colleagues in Wigan Council, Rochdale Borough Council and The Children’s Society for their ongoing input and passion for evidence.

Thanks also to Sue Botcherby and Sara Scott for their input and support in the first version published in 2015.

Our gratitude to Jessica Eaton who revised this scope in 2017 to reflect new evidence and practice wisdom. A labour of love indeed.

Limitations of this review

This evidence scope is not a systematic review; accordingly, the quality of each study or report was not assessed. However, it draws largely on published research, prioritising peer-reviewed literature where possible, and uses credible sources for policy literature and other sources of information. The literature used is largely recent, and, if not, then of enduring importance.

A full description of the methodology can be found in Appendix A.

This evidence scope was undertaken for the specific purpose of supporting colleagues involved in the Greater Manchester CSE Innovation Project in their efforts to redesign CSE services. As such, its purview has developed over time in response to their feedback and lines of enquiry; it does not offer a comprehensive review of all evidence related to CSE.

This revised edition, published in 2017, reflects the emergence of new evidence and practice wisdom.

This evidence scope formed one element within a range of research activities in the overall project in Wigan and Rochdale, including case file analysis, biographical interviews with young people, focus groups with staff and peer review.

The messages within this scope reflect the review team’s interpretation of the evidence.

1. Introduction

This scope aims to support local areas in the continual development of child sexual exploitation (CSE) services by reviewing and critically appraising relevant evidence. The scope proposes six key principles for effective service design (see Section 9).

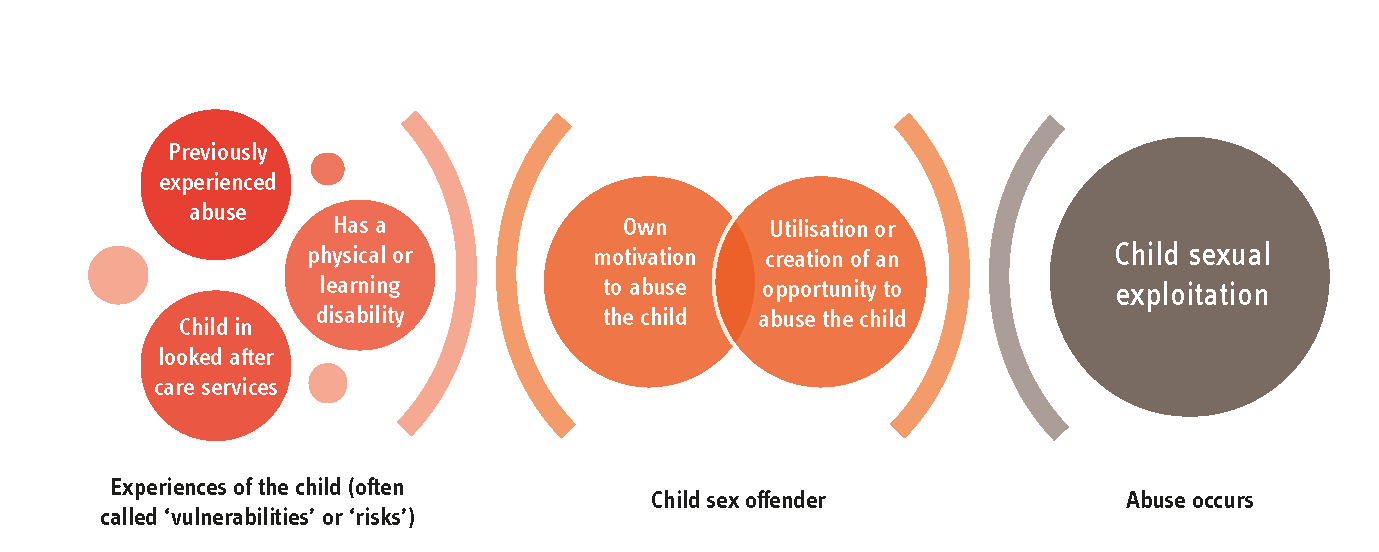

Whilst this scope focusses on practice with children, it is the identification, early intervention, investigation, prevention, prosecution and monitoring of child sex offenders that will ultimately protect children. Professionals working in legal services, policing and the criminal justice system all have a critical role in reducing the abuse of children in society. The intervention and prosecution of sex perpetrators is, however, outside of the remit of this evidence scope. For those keen to explore these issues, there is an established body of empirical research, theories and practice evaluations focusing on child sex offenders and abusers in forensic psychology and criminology; in addition to practice guidance and advice for police, custodial services, probation and the wider network of practitioners.

Protecting children and young people from sexual exploitation is a challenging area of practice across all sectors, including health, education, the police and third sector organisations, as well as social care and social work. It is a sensitive phenomenon around which there is still uncertainty about how to respond, in part due to its complexity.

Although CSE may be a complex area, what is not in question is who causes CSE. The blame lies clearly with the perpetrators who exploit young people and cause them harm; this is irrespective of the behaviour or circumstances of the victim. This scope explores many factors that focus on young people, but this should not detract in any way from the fact that responsibility for the abuse lies with the perpetrator. Discussions within this scope actively challenge assumptions, practice and language that may contribute to victim blaming of children affected by CSE.

Throughout the scope we use the terms ‘young person’ and ‘young people’ as well as ‘children’. Whilst it is vital to recognise that all persons under 18 years old are children, this scope presents a synthesis of findings and issues from different fields and these tend to adopt different language. In CSE, a great deal of the literature and practice focuses on older children, as this group appear to be those most likely to be affected by CSE 1, and so often uses the term ‘young people’. The term ‘young person’ is also the preferred term used in participation (a topic which is discussed throughout this scope) and tends to be the terminology used by older children themselves. Given the imperative to challenge the notion that any child can ever bear responsibility for abuse and exploitation, using these terms interchangeably presents some difficulty, especially as the term ‘young person’ might be interpreted as conveying more agency and responsibility than the term ‘child’. However, this scope tries to convey the language used by the particular authors of each piece of evidence or research; therefore it will vary throughout.

This approach of adhering as closely as possible to the original source presents other challenges. Some research in this area has been produced in countries, or at a point in time, where terms that would now be considered inappropriate have been used (such as ‘child prostitution’ to describe child sexual abuse and exploitation). This scope takes the view that despite this uncomfortable use of language, the research findings are often valid and useful.

It is important to acknowledge that the extent of CSE in the UK is significant, and that awareness of the scale of the problem, both in the UK and internationally, has increased in recent years (Chase and Statham, 2005; OCC, 2013a). While societal awareness of CSE is increasing, the question of how best to tackle it remains a challenge, not only for social work professionals but for all practitioners across the children and young people’s workforce also.

Social workers have a statutory duty to safeguard children and young people. They are also the leads in inter-agency and inter- professional working when significant safeguarding concerns arise (HM Government, 2015a). However, tackling CSE is an issue of multi-agency responsibility. The centrality of partnership working is evident in terms of inter-agency and professional collaboration, information sharing across sectors and across geographical boundaries, and working in partnership with local communities, families and young people themselves (Laming, 2009; Munro, 2011; HM Government, 2015a).

Laming (2009: 36) highlighted that in order to safeguard children and young people from harm, relationships between practitioners are crucial:

Too often, agencies co-operate and share information with social services out of ‘good will’ rather than in recognition of their statutory duty. In any case, statutory duty is not enough on its own. In order to address CSE effectively, there needs to be a cultural shift. As the government’s recent paper on tackling child exploitation notes, what is required is:

Put simply, this is bigger than social workers.

All service providers in touch with young people and their families have a role in identifying and working with sexually exploited young people and in disrupting and prosecuting abusers (Pearce, 2014; HM Government, 2015a, 2015b; Beckett et al, 2017). Practitioners at all levels and across all agencies – as well as the wider community – must be able to recognise and respond to concerns related to the various manifestations of CSE. Clear strategies for intervention are needed, resourced at both an operational and strategic level, together with an approach that enables integrated working.

This evidence scope is, therefore, concerned with gathering evidence that supports interventions and multi-agency and inter- professional approaches to working to improve outcomes for young people who may be affected by CSE. Wherever possible, this includes a preventative and early help perspective. It draws on a range of national evidence and perspectives in order to provide a balanced overview for service design.

It was commissioned by Wigan and Rochdale councils, as part of the Greater Manchester CSE project, funded by the Department for Education Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme. It was revised by Jessica Eaton in 2017 to reflect new evidence and emerging practice wisdom.

Aims of the scope

This scope offers a set of principles drawing on evidence from a variety of sources to underpin the development of a new service. The main aims are to:

- Review the literature in relation to CSE

- Identify the key messages and implications for service design, practice, leadership and, where possible, commissioning

- Identify key principles to inform service developments and ways of working in practice.

This rapid scoping exercise focuses on the following key areas:

- How the problem is interpreted, defined and contextualised within contemporary policy and practice, and within society

- Issues of recognition and response

- Considerations when assessing the needs of children and young people at risk of, or experiencing, CSE

- Central tenets of effectiveness when working with these children and young people, including assessment and interventions for both the short and long-term reduction of harm, and the role of families

- The support needed for the workforce to operate effectively in this area

- Participatory approaches in practice and service design – the benefits and theoretical underpinning.

It is important to emphasise, however, that this is not a systematic review; the literature is too wide ranging and no scientific approach has been applied to assessing the reliability and validity of any research findings referred to. However, the scope does draw on peer- reviewed published research where possible, thereby offering a degree of assurance regarding the validity of the data. The scope does not include: international direct comparisons; case studies from primary research; the views of parents, families and young people 2 (other than those reported in the existing literature). While there has been considerable media interest in the issues of CSE, detailed analysis of media reports is outside the remit of this work.

A more detailed overview of the methodology is detailed in Appendix A.

2. Background and context

This section outlines definitions, provides the contextual background and historical contemporary perspectives, and defines the ‘problem’ within the current UK context in order to inform understanding of recognition and responses to CSE. Subsequent sections will focus on identification, assessment, interventions and young person-centred approaches to developing services.

2.1 Definitions

Definitions provide the conceptual framework for practice within which legislation, policy, data collection and research are located. Whilst the definition of child sexual abuse (CSA) has remained fairly stable for a long period of time, the definition of child sexual exploitation (CSE) has been in a state of evolution in recent years. Currently, the definitions draw a distinction between CSE and CSA, so each one will be discussed here.

Looking at policy definitions, the government’s guidance Working Together to Safeguard Children states that sexual abuse:

The definition of CSA provides detail of abuse and offence types and also seeks to break down some important assumptions within it. It should be noted that the definition of CSA clearly positions the abuse as harmful and illegal. It makes sure that CSA can be defined without the presence of other physical violence and also states that the child may or may not know what is happening to them. The final sentence is also a reminder that perpetrators of CSA are not always male, an important point in light of evidence suggesting female child sex offenders are under-identified (Elliott, 1995).

The terminology used in relation to CSE (and its definition) has been in a state of flux for some time. This recently underwent further iteration in February 2017 with the government publishing a new definition (see below). The abuse now known as CSE has been written about since at least 1856 (Hallett, 2017) and terminology has come a long way since the term ‘child prostitution’ which was used widely until pressure from feminist and child rights organisations meant that the term came under increasing scrutiny. It was briefly changed to ‘abuse through prostitution’, then ‘commercial exploitation’ of children and, now, ‘child sexual exploitation’. Practice terminology and legal definitions were not adapted in tandem, however; until 2015 the Sexual Offences Act 2003 still used the term 'child prostitution'.

This offers some insight as to why the definition of CSE now looks rather different from the definition of CSA, despite CSE unarguably being a form of child sexual abuse. This evolution could also offer insight into the sticky concept of ‘exchange’, which is discussed further below. A further criticism of the evolving language around CSE is that it is becoming ‘hygienic’ and abstract, whereby the definition does not represent the true harm, violence, injuries and death of children, but describes a vague process of exchange with no reference to harm or trauma (Gladman and Heal, 2017).

Just as the terminology has been evolving, so too has the definition of CSE. There has been debate as to whether a definition of CSE is needed, especially now that the new definition states firmly that CSE is a form of CSA (Shuker, 2015). In February 2017, the government issued a new definition of CSE:

The statutory definition is now applied and is considered the main definition of child sexual exploitation 3. Previously there have been a number of different definitions of CSE, including definitions written by The Children’s Society, Department for Education, Association of Chief Police Officers and the NWG (formerly The National Working Group for Sexually Exploited Children and Young People).

Until the change in February 2017, this is how the NWG defined the sexual exploitation of children:

The definitions of CSE and CSA look very different and may be subject to further change and evolution as the evidence base matures. A key distinction explored by Beckett and colleagues in the ‘extended text’ 4 of the national CSE guidance (Beckett et al, 2017) is that CSE involves a power imbalance and an exchange of something ‘tangible or intangible’. However, it is important to note that CSA always occurs with a power imbalance (and this is included as a footnote by the authors); but what about the exchange? Recently, survivors from Rotherham have been challenging the notion of ‘exchange’ by arguing that the concept is offensive to victims and survivors because it reframes the violence and abuse as reciprocal (Woodhouse, 2017). It can be argued that CSA involves some form of exchange, especially that of intangible exchange such as being made to feel special, keeping an important secret, buying toys, or being treated better (or worse) in order to keep the child from identifying, understanding or disclosing their abuse to someone else. This point is also acknowledged by the authors and others, who note the concept of exchange is not unique to CSE and that the definition has become too vague (Shuker, 2015). A critical point is that despite ample evidence that exchange is used by child sex offenders as a method of grooming, the receipt of goods, gifts or money has led some to consider that a child may be more complicit or consenting in cases of CSE than in CSA cases, where the child is more clearly seen as a victim and the exchange is more clearly seen as a method of grooming and control. This tension, wherein acknowledging the exchange dynamic can lead to a less protective response, is arguably not a definitional one but an educative one (Beckett and Walker, forthcoming).

In practice, this difficulty means that many cases of CSA could be defined as CSE and many cases of CSE could equally be defined as CSA. Whilst there is some benefit to exploring the distinctive elements of CSE, it is also argued that the creation of a definition of CSE, as the only legislated sub-category of CSA, can fuel an unhelpful dichotomy between CSE and other forms of CSA (Beckett and Walker, forthcoming). The importance of those definitions and perceptions of each of the terms becomes more obvious when we begin to explore the responses to these two different yet connected types of abuse.

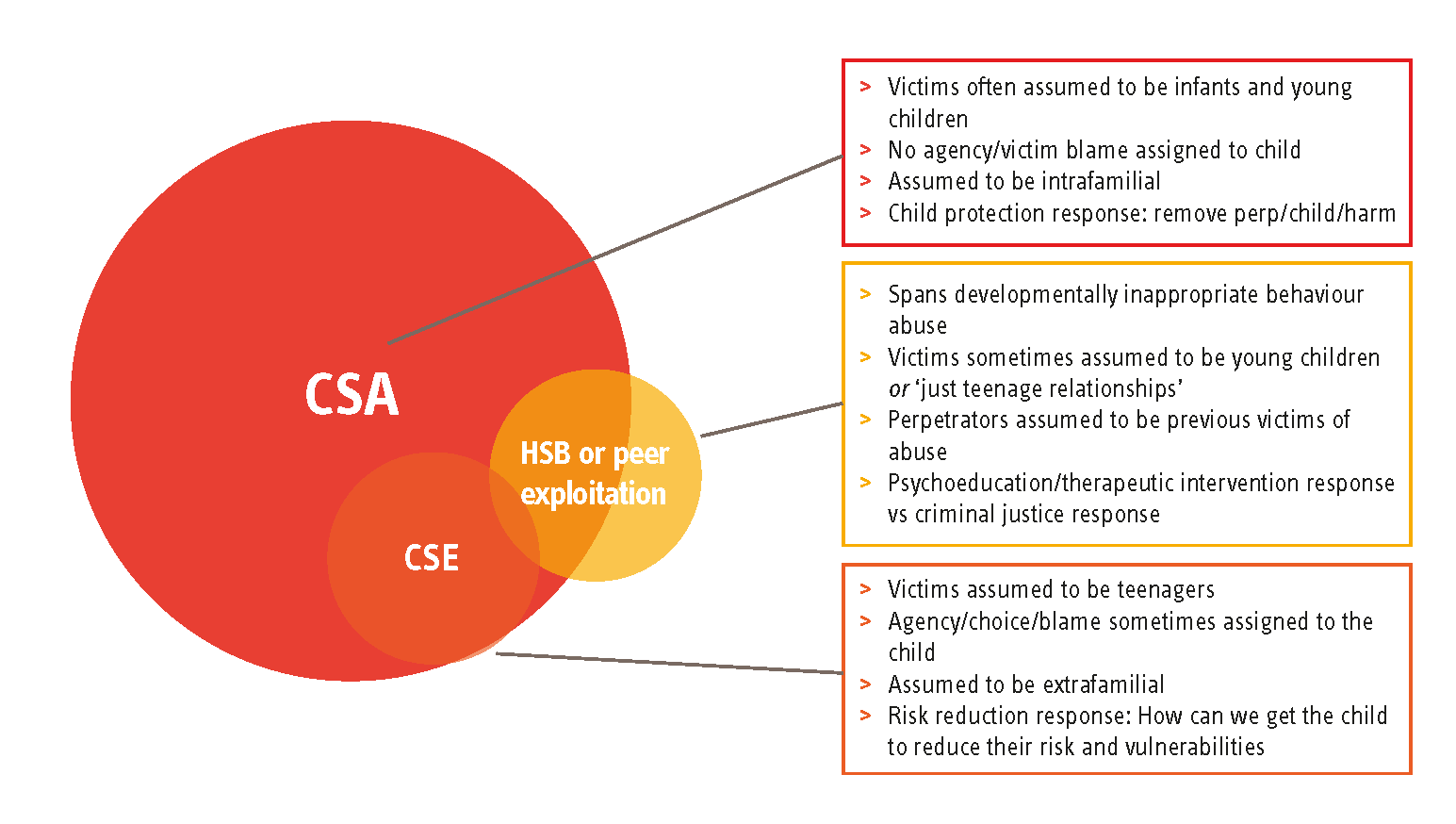

Figure 1.1: CSE and HSB as a type of CSA (Eaton, 2017)

Figure 1.1 presents CSA as the overarching form of sexual abuse within which harmful sexual behaviours (HSB) or peer exploitation and CSE exist and overlap. It is important to note that some evidence asserts that most CSA is intrafamilial, with 90 per cent of victims being sexually abused by someone in their family or close support network5 – though such estimates are challenging due to the hidden nature of sexual abuse and the changing perceptions of exploitation and HSB. HSB spans a spectrum of behaviours from developmentally inappropriate through to abusive (Hackett, 2014).

Child abuse, specifically harm to younger children within the family context, is arguably the construct on which the child protection system, procedures and policies were built (Bilston, 2006). When practitioners, authorities and the general public talk about CSA, there is a general assumption that it affects small children and infants within their familial home, usually being perpetrated against by a male family member. The response is often swift and aims to remove the child from all harm to a place of safety. It is unlikely that young children who have been sexually abused by an adult family member would be blamed or assigned agency in their abuse.

Child sexual exploitation, having evolved from all of those definitions and terminology – and subject to high-profile media coverage of particular cases – tends to conjure up a very different image. Victims are assumed to be teenagers (specifically teenage girls), being exploited outside of the familial environment. Children are assigned a level of agency, choice or blame which is different to children affected by CSA, a point regularly featured in serious case reviews of child sexual exploitation (Bedford, 2015; Jay, 2014; Coffey, 2014). Some of this results in questions being asked of the child that imply blame or responsibility. Arguably, a stark difference is seen in the systemic response to the child, in which they are assessed as a ‘risk’ and then supported to reduce that ‘risk’ and/or their ‘vulnerabilities’ until the child is deemed safe. This risk reduction response places considerable responsibility within the child to safeguard themselves from further harm.

Harmful sexual behaviours and peer-on-peer abuse is different again, with HSB often assumed to be displayed by young children who have previously experienced sexual abuse and are therefore copying those behaviours with other children. Work by Hackett (2014; 2016) and others suggests a much more complicated picture. Vosmer et al (2009) and Hackett (2016) argue that not all children who abuse peers or display HSB have experienced sexual abuse and that HSB is correlated with a range of adversities such as witnessing violence in their family, isolation and environmental factors. In addition, it is important to consider emerging issues for this generation of children such as watching porn, being exposed to sexually aggressive media and the overall hypersexualisation of society which may be influencing behaviours of children (Vosmer et al, 2009). When children are displaying developmentally inappropriate sexual behaviours and/or found to be abusing other children, it can be difficult to achieve a response that balances the needs of both the child instigating abuse and the child experiencing it. In general, effective responses tend to be holistic and educative in nature, resilience-focused and are likely to include therapeutic intervention (Hackett, 2014).

To conclude, current definitions are not perfect and it is likely that they will continue to evolve for some time. It is important for practitioners to recognise the definitions of CSA and CSE, and to understand the potential distinctions between the evolving definitions; however, endless debate about what constitutes CSE could even be detrimental to practice (Beckett and Walker, forthcoming). Professionals are likely to require guidance, but this should be employed as the scaffolding that supports child-centred evidence-based responses to harm, and not as a restrictive and instructive definition which limits responses to harm and access to services.

Reflection pointers

- Are practitioners across all agencies aware of the distinction between child sexual abuse and CSE, while recognising that CSE is child sexual abuse?

- How do we know that practitioners are sure of what constitutes ‘sexual exploitation’?

- What else can we do to support practitioners to respond effectively to concerns about children when the type of sexual abuse may not be clear?

Background – The extent of the problem, incidence and prevalence

The scale of the problem has been highlighted in recent years. An inquiry by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner into CSE by gangs and groups identified 2,409 children as victims of CSE in little more than a year (OCC, 2012: 9); a further 16,500 children and young people were identified as being at risk of CSE. What has also emerged is that the risk of sexual exploitation begins earlier than was previously thought or acknowledged, with clear evidence that adolescents as young as 12 or 13 are affected by contact sexual abuse and children as young as 8 years old affected by online exploitation (Barnardo’s, 2011a; Ringrose et al, 2012; CEOP, 2007). The interim report of the OCC’s two-year inquiry into the nature and extent of CSE begins by stating:

It is difficult to gain an accurate understanding of the prevalence of CSE because, historically, many survivors have not come forward and because definitions and perceptions have changed. Furthermore, CSE is not always listed as a separate category in child protection procedures or crime reporting (OCC, 2012). A number of reports have attempted to estimate the prevalence of CSE. For example, the Department for Children, Schools and Families identified that 111 out of 146 Area Child Protection Committee districts had cases of CSE, with a higher prevalence of sexual exploitation of girls than boys (DCSF, 2009). The National Working Group found that over a 12-month period, 53 specialist services worked with 4,206 reported cases of CSE (NWG, 2010). In 2016-17 Barnardo’s alone supported 3,430 people through their child sexual exploitation direct support services (compared to 2,486 in 2015-16)6.

Sexual grooming via the internet and mobile technology is also widespread, making it even harder to assess prevalence accurately (Barnardo’s, 2011b; CEOP, 2013; Chase and Statham, 2005; Radford et al, 2011). Online threats to children and young people include the proliferation of child abuse images, online exploitation, transnational child sexual abuse, and contact child sexual abuse initiated online (CEOP, 2013). It is common to find areas in which almost all of the cases of CSE involve online exploitation and online grooming (Palmer, 2015). (The discourse around pornography and sexualisation is explored later in this section.)

Beckett et al (2017) succinctly note that while the prevalence data in CSE is generally unreliable due to low levels of reporting, it can be reliably assumed that CSE is happening in all areas of the UK and online.

Research in forensic psychology has been exploring what the evolution of the internet has meant for child sex offenders. O’Connell (2003) suggested that the internet has increased accessibility, vulnerability and opportunity. The literature includes exploration of offence types, behaviours and victims of online sexual exploitation. An important study by Whittle et al (2013) synthesised evidence from a range of studies. It showed online sex offenders varied widely in their grooming processes and techniques, had different goals (contact-driven or fantasy-driven offending) and that 77 per cent of sex offenders used a range of simultaneous communication methods to manipulate their victims, such as email, text, social media and phone calls.

Reflection pointers

- How do we know that our data, and that of neighbouring local authorities and partner agencies, is sufficiently accurate to identify need and plan service responses?

- How, if at all, do we capture the scale of online exploitation?

- What could be done to build better local evidence of the scale, types and impact of online exploitation?

Tackling CSE: what does success look like?

As a form of child sexual abuse, child sexual exploitation has a largely similar impact to CSA in terms of the symptoms, behaviours and harm it causes. In theory, therefore, success in ‘tackling’ CSE should look much the same. There are some considerable differences, however. Many cases deemed to be CSE include one or more abusers who is/are external to the family home and who can sometimes be difficult to identify. Practice responses to CSE commonly include the decision to remove a child from their family environment (Beckett, 2011a) because an external sex offender is abusing them; this is framed as the child being removed for their own safety and wellbeing, despite the family environment itself not being harmful. Victims of CSE are also too often met with victim-blaming responses and judgements that frame the child as ‘promiscuous’ and badly behaved (Jay, 2014; Coffey, 2014; Bedford, 2015). There are also systemic differences in the way CSE is responded to, with responses tending to follow a set of specific CSE procedures, strategies and policies.

In 2006, Scott and Skidmore conducted a commissioned evaluation of Barnardo’s CSE services. They stated that successful outcomes for children affected by CSE included increased awareness of CSE, self-protective resources and a reduction in ‘risk behaviours’ (listed as going missing and conflict with parents and carers). They argued that positive outcomes for a child would be ‘an improved ability to recognise risky and exploitative relationships’, ‘protecting themselves appropriately’ and ‘not associating with controlling/risky adults’. These outcomes were then published to guide strategic leaders and practitioners towards what a CSE service should be aiming for.

However, whilst some of these outcomes would be of benefit to any child, the evidence base and practice wisdom has changed since 2006. Accordingly, greater attention is now paid to ensuring that language does not inadvertently contribute to children being ascribed responsibility or blame. In this spirit, it is valuable to reflect on and critique the way that language such as ‘protecting themselves appropriately’ and ‘not associating with controlling/risky adults’ and ‘reducing risk-behaviours’ can serve to position the child as both the source of the problem and the source of the solution.

In light of this approach, the successful outcomes of ‘tackling CSE’ are now being described in developing local CSE strategies and organisational statements. These include educative work with the whole child population, swift identification and reporting, disrupting and removing the source of risk (the sex offender) and supporting the child with their psychological, practical and social recovery, including building resilience, processing their trauma and re-empowerment after a period of serious harm. Barnardo’s recently developed 10 year CSA strategy moves clearly towards ensuring that activity to protect children; centres on trauma informed approaches, working systemically with the adults and systems to address harm and crucially ensuring that young people have agency and that their voices lead the support process. (Barnardo’s, forthcoming).

When determining safety-focused outcomes, the work of Shuker (2013a) is useful in its argument that physical, relational and psychological safety are all vital for safeguarding the welfare of young people affected by CSE.

Tackling CSE: some of the challenges

What is clear then is that currently, CSE is not an easy issue to tackle. Moreover, young people do not always understand that they are being abused or exploited (DCSF, 2009; Beckett et al, 2017), a further challenge for those seeking to identify and address CSE (see the discussion on disclosure in Section 4). Whilst to some extent this reflects childhood naivety and the general vulnerability of being a child researchers point out this lack of understanding and knowledge is even more profound for children with learning disabilities (Franklin et al, 2015) – it would be an oversimplification to ascribe low levels of self-identification and disclosure to children’s lack of awareness alone. Adults who are being sexually abused or experiencing domestic abuse also find it hard to understand what is happening to them and to identify or label their experience as sexual abuse or rape. Children are not the only ones who struggle to identify and name their experiences; we shouldn’t expect them to be able to do so if research shows that adults also find it difficult (Miller et al, 2007; Heath et al, 2011).

While there is increasing awareness of CSE and the individual, family, societal and environmental factors that increase a young person’s vulnerability, there is a dearth of evidence for social workers and the wider children and young person’s workforce in the UK to support effective service delivery (Brodie et al, 2011; Barrett et al, 2000; Dodsworth, 2014). It is also the case that too many services have failed to respond to recommendations set out in statutory guidance, despite sexual exploitation being one of the many key problems facing young people who may already be known to services (Pearce, 2014; Ofsted, 2014; HM Government, 2015b).

As noted, challenges also stem from the fact that the child protection system itself was designed with young children experiencing harm within the family in mind (Bilston, 2006). It is therefore arguably not always helpful as the dominant construct for addressing contemporary adolescent risk (Hanson and Holmes, 2014). There is a need for greater exploration and research around the correlates and contexts of CSE, and the appropriateness and adequacy of existing child protection procedures alone to address CSE is under scrutiny (Chase and Statham, 2005; Hanson and Holmes, 2014).

A strong example of this issue is presented by PACE (2014) who published The Relational Safeguarding Model in response to the criticism that the child protection system is inadequate when dealing with CSE. One of the core arguments is that the child protection system and theory assume that the root cause of the problem lies within the child, the home or the parenting. So when CSE is perpetrated by an external sex offender, the child protection system (and those trained within it) can erroneously search for reasons and causes of the abuse within the child, home or parenting.

There is consensus in the literature that the problem requires practitioners to take an integrated and coordinated approach to the resourcing, investigation and management of CSE, at a national and local policy, practice and strategic level (Department for Education, 2012; Dodsworth, 2014; Pearce, 2014). However, this kind of multi-agency safeguarding approach at all levels can be challenging, and resource pressures in some areas are making it yet more difficult to achieve (Baginsky and Holmes, 2015). The challenges of establishing shared data sets across agencies are well documented, not least for Local Safeguarding Children Boards (Baginsky and Holmes, 2015) who have been expected to play a leadership role in developing a strategic response to CSE. These challenges may equally affect the ‘flexible’ local multi-agency arrangements for safeguarding that will replace LSCBs 7 . Added to this is the challenge that CSE spans geographical areas, so the lack of clarity and consistency in data gathering creates challenges for effective analysis and triangulation across borders. Despite these challenges, police forces have been working together to develop intelligence recording systems and intelligence sharing protocols (such as Operation Striver 8) so that information held on victims is also shared across police force areas, rather than remaining the sole information of one force. When children are being trafficked during sexual exploitation, the sharing of information across force borders is vital.

There is much to learn from assessing the literature and exploring the more effective elements of service responses – as this scope seeks to do. However, there is no one gold standard model for service design and delivery.

Reflection pointers

- How do our information-sharing protocols and data collation systems between agencies enable consistency, comparison and triangulation?

- How do we capture what is working in relation to local CSE responses (and why it is working) in order to build our evidence base?

- What is being done to ensure that local innovation is grounded in evidence, and that learning from implementation is captured?

Key messages

- Local areas need to use local data and local knowledge along with available evidence from research, theory and practice, to design a service response that best meets local needs while also addressing national agendas and policy.

- Effective data collation and sharing protocols between agencies and between areas is vital to identify need and plan responses.

- A continuous evaluation and audit cycle built into services is vital in order to build knowledge of what is effective.

- Service design and delivery needs to take into account the particular needs and circumstances of young people locally, rather than follow rigid models.

- There is no gold standard model for service design and delivery. Nevertheless, there is much to learn from assessing the literature and exploring the effective elements of service responses.

Historical perspectives and their influence on contemporary approaches

Although recent high-profile cases such as Operation Span, Operation Retriever and Operation Bullfinch in 2012-13 9 have brought CSE squarely into the public domain, CSE is not a new phenomenon (Coffey, 2014). Hallett (2017) provides evidence that CSE was being discussed – and being clearly identified as the sexual exploitation of children – in 1856 by writers who were concerned that ‘child prostitutes’ were really being abducted, used and raped. CSE was later framed within arguably narrow salvationist, paternalistic and welfarist approaches and concepts of child (sexual) abuse, stranger danger, ‘child prostitution’ and grooming (Melrose, 2013; Hallett, 2013; Cockbain et al, 2014). As was once the case with other models or definitions of child abuse, the existence of CSE as a specific concern has been hidden or denied (Corby, 2006; NSPCC, 2013a). This is significant because concerns can only be tackled when there is acceptance that a problem exists. Acceptance of the problem needs then to be followed by a shared definition of that problem, accompanied by strategies, systems and policies to address it.

Until the 1990s the main child protection concerns were with intra-familial abuse (primarily physical, sexual and emotional abuse) and neglect. Concerns then began to emerge about extra-familial abuse, including organised sexual abuse and ‘child prostitution’. This shifted and extended the focus of practice, but practice has attempted to evolve within the confines of the original definitions of child protection. The period from the mid-1990s to 2008 can be seen as a time when policy shifted from a narrow child protection focus towards a more family and child-focused orientation (Gilbert et al, 2011).

Parton (2014) argues that in order to ensure systems work – both to safeguard children and young people more widely and to respond to those who need protection from harm – policy and practice must have a children’s rights perspective at their core. Such a perspective recognises that there are a wide range of significant and social harms that cause or collude with child abuse and maltreatment, and many of these are clearly related to structural inequalities (Bywaters et al, 2017). Featherstone et al (2014) have contributed to this debate, challenging the ethics and values of an authoritarian approach with multiply deprived families, and urging a shift in child protection practice and culture in order to recognise children as relational beings.

The existence of child abuse in history, including both CSA and CSE, is indisputable; what remain contentious today is the extent of CSE and its interpretation. CSE now has a high profile. It generates considerable concern within communities and has led to multiple policy and professional initiatives (Barnardo’s and LGA, 2012; OCC, 2013a; Department for Education, 2012; Department of Health and PHE, 2015; HM Government, 2015b; NSPCC, 2013b; Royal College of Nursing, 2014; Pearce, 2014). As with child sexual abuse, CSE has been a difficult subject to talk about and therefore difficult to address (NSPCC, 2013b). It was not until the late 1990s that UK governments and policymakers gave CSE due attention. Until recently, different models of exploitation were contextualised as other forms of child maltreatment or located within ‘child prostitution’ as child protection concerns (Pearce, 2009a). Significantly, the OCC’s inquiry into CSE in gangs and groups (OCC, 2012) recommended that use of the term ‘child prostitution’ should be removed from government documents and strategies and from legislation. Coffey (2014) further recommended there should be no references to child prostitution in any legislation (see also Barnardo’s, 2014b: 11). They have succeeded in this, achieving much more than simply a shift in language but arguably prompting also a shift in attitude. Language matters; it both reflects attitudes and can form attitudes. Just as with the now widely criticised term ‘child pornography’, when child abuse is erroneously conflated with adult activities we risk inferring consent from, and blame towards, the child victim.

Despite this increased attention, however, some uncertainty about what constitutes CSE remains (Melrose, 2013). How CSE is defined or interpreted is in turn related to wider issues in society. And although the problem is not actually a new phenomenon, there is some newness to the issues that surround it. For example, new technologies and media provide easier access to pornography, not only providing new tools for perpetrators to exploit and abuse young people, but arguably shaping young people’s perceptions of sex as well (CEOP, 2013). So in the context of CSE, there is a genuinely ‘new’ element to a long-standing but only recently recognised phenomenon; this brings new complexities and challenges for practice.

Key messages

- Concerns can only be tackled when there is acceptance that a problem exists. Historically, as with other forms of child abuse, denial and ‘blind spots’ to the existence of CSE have contributed to the challenges of defining and addressing CSE.

- Language matters; it both reflects and can inform attitudes. The use of inappropriate language can act as a significant barrier to protecting young people from CSE.

Contemporary conceptualisations

Contemporary conceptualisations, borne out of historical perspectives but advanced by recent research and developments in practice, recognise that although CSE is a form of child abuse, it is helpful to understand the many factors that contribute to the existence of and misunderstanding of CSE. When considering how best to configure a service response, it is important to reflect on a number of different perspectives and factors. These include societal reactions to the increased concern around CSE, the role of power and gender, and the ways in which risk and choice are conceptualised. Online abuse and pornography are also considered.

Media coverage and myths

The recent media attention around CSE has implications both for contemporary understanding of CSE and responses to it. When amplified by media representation, public outrage, however understandable, has the potential to do harm, not least in its impact on the workforce – as Jones notes in his discussion about the response to Peter Connelly’s death (Jones, 2014). At times of widespread public outrage, there is a need to be alert to discourses and the language used by politicians, public leaders, the media and professionals. This is significant because it is often the young person who is demonised and their behaviour seen as criminal, when in fact they are the vulnerable and exploited victim (see, for example, the serious case review authored by Bedford, 2015).

Another impact of widespread media coverage of CSE is the development of stereotypes – the more times a story is reported or told in a specific way, the more likely it is that the general public and professionals will absorb a stereotype of offenders, victims and abuse typologies (Flowe et al, 2009; Shaw et al, 2009). An example is the significant public misconception that CSE offenders are Pakistani males, which overlooks the complex picture of child sexual abuse. Perpetrators and victims of CSE are known to come from a variety of social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds and CSE occurs in both rural and urban areas (LGA, 2014). It is argued that the national media have paid considerably less attention to cases involving groups of white British perpetrators, even when the crimes and sentences are strikingly similar (Operation Kern vs Operation Retriever 10). For victims, it has meant the development of an impactful stereotype of a young white girl, generally in local authority care, known to multiple services and with overt vulnerabilities and ‘promiscuous’ behaviours (Fox, 2016). If professional resources (such as films, posters, websites and support materials) echo these victim and perpetrator stereotypes, this can exacerbate stereotyping. When it comes to abuse typology and grooming methods, the media have employed words like ‘sex gangs’ and ‘child sex slaves’ and ‘paedo gangs’ – meaning that the media have created a stereotype of organised crime gangs of paedophiles (usually this word is being incorrectly used in place of ‘sex offender’ 11) using children in a highly organised manner as sex slaves. This is a far cry from the real types of case that workers in the UK are holding; according to some researchers, only eight per cent of sex offenders abuse children with another offender (Brayley and Cockbain, 2012).

Conversely, for local areas seeking to address CSE, the increased media attention might also present an opportunity to strengthen efforts to raise public awareness and increase understanding. To realise these potential benefits, information must be accurate, free of bias and must not perpetuate unhelpful or damaging stereotypes, not just of children but also of perpetrators and offences. Careful attention must be paid to the way any kind of media reporting, awareness raising, resources and films are developed so these stereotypes do not continue to lead to blind spots and gaps in responses.

Myths around CSE

As discussed above, insensitive, inaccurate or over-simplified media stories can also play a part in sustaining myths around CSE. In addition to the myth that CSE only involves certain ethnic cultural communities, other myths also prevail, so it is especially important that practitioners are aware that:

- CSE is not exclusively about adults abusing children – there is increasing concern around peer-on-peer abuse and the risks that young people face within their own social settings, such as schools (Firmin, 2013).

- Both males and females are abused through CSE – similarly, both males and females are perpetrators.

- Perpetrators may be previous or current victims themselves.

- CSE can take place online and offline or both. Sex offenders can also groom and exploit exclusively online without any intention of ever meeting the child – online grooming should not necessarily be seen as a precursor to contact offences.

- CSE can be perpetrated by individuals or by groups.

- There is no typical CSE case; CSE takes many different forms.

- Children who are sexually exploited do not always have some sort of underpinning vulnerability; looking for evidence of the ‘vulnerability’ that ‘caused’ the sexual exploitation can lead to (or collude with) victim blaming.

- Sex offenders do not always seek out opportunities to abuse vulnerable children, they create new opportunities to abuse and they create new vulnerabilities that did not exist before.

Traditionally, perpetrators of CSE have been depicted as strangers who appear threatening and dangerous. This perception is inaccurate (Lalor and McElvaney, 2010) and can impede recognition of CSE, possibly leading to resources and interventions being misdirected to other areas of service intervention or child protection. In fact, reports show that perpetrators are often known to and indeed close to the victim; through a process of grooming and coercion, they manage to engage in sexual abuse and exploitation of the child (CEOP, 2013), which mirrors the offender types in CSA.

The notion of ‘dual identity’ in some young people affected by CSE can present particular challenges. As with harmful sexual behaviours (not specifically CSE) perpetrated by children and young people (Hackett, 2014), it is important to note that there is not always a neat distinction between victim and perpetrator. For example, the Office of the Children’s Commissioner found that six per cent of victims reported in their call for evidence were also perpetrators (LGA, 2014: 19 citing OCC, 2013a). It is also important to keep in mind that although children may appear to be willing accomplices in the abuse of other children, this should be seen in the context of the control exerted by the perpetrator. When children are being exploited by adults to recruit other children into abuse, they are still being exploited and groomed – simply for a different purpose.

Key messages

- Societal alarm and media coverage is understandable but can have unhelpful consequences, such as stereotyping and over-simplifying the issues. It can also serve to undermine professionals’ understanding and confidence.

- Societal alarm and outrage might, however, provide an opportunity for promoting greater understanding of CSE, by meeting increased public understanding and concern with accurate and informed awareness raising.

- Everyone involved in configuring, designing and leading service responses to CSE, as well as practitioners themselves, must be alert to myths surrounding CSE. It is essential that the way CSE is represented locally does not encourage or perpetuate ‘blind spots’ or simplistic stereotypes, and so place young people at risk.

- CSE is not perpetrated exclusively by adults. Young people can also be perpetrators; and young perpetrators may also be victims.

Reflection pointers

- Does any of the language used by senior staff inadvertently reinforce inaccurate or unhelpful stereotypes of CSE? For example, by ignoring female perpetrators, or by assuming there are always clear-cut distinctions between young perpetrators and victims of CSE?

- Is sufficient attention being paid locally to CSE perpetrated by peers?

Power, gender, pornography and sexualisation

As we saw in our discussion of definitions, it is currently argued that what differentiates CSE from other forms of abuse is the concept of ‘transactional sex’ or ‘exchange’ of sex for money, goods or something else (Beckett, 2011b). For the child, this means receiving or believing they will receive something they want or need, or something they think they want or need (Beckett et al, 2017). The suggestion that the child may ‘gain’ something from this transaction may be misinterpreted by adults and serve to disguise the power imbalance in play between perpetrator and victim (Beckett and Walker, forthcoming), which is arguably more readily recognised in all other forms of abuse. The concept of exchange (which, as noted previously, is contested by some) creates a particular power imbalance in the relationship, which in itself is exploitative and unhealthy for the young person, and can create an illusion of reciprocity in the minds of young people and in the minds of practitioners. The power that perpetrators wield over victims can be extremely potent (Bedford, 2015) and may not be recognised by practitioners, further heightening risk. Professionals must be conscious of this relative power when seeking to engage young people in help (RCGP and NSPCC, 2014).

There are a number a ways in which children and young people are exploited that raise uncomfortable issues about adult power and responsibility, including those relating to how the power of professionals can be experienced by victims and families. There are stark examples of practitioners not fulfilling the duties that come with occupying powerful positions (Bedford, 2015; Jay, 2014). There are also examples where relative power and status between different professional groups is said to have contributed to CSE not being addressed (Casey, 2015). Power is significant also in how families of CSE victims experience support. There are those who argue that current child protection practice and culture ignores, or exacerbates, the relative powerlessness of families who are often already experiencing multiple manifestations of disadvantage (Featherstone et al, 2014). Given that the child protection system remains the dominant construct for addressing CSE, and in light of the sense of powerlessness that parents of CSE victims report, it is important to consider whether practice with parents is intensifying this power imbalance. Recent work published by the Centre of Expertise for child sexual abuse draws further attention to this issue. According to an evidence scope 12 exploring the support needs of parents of sexually exploited children and young people, statutory safeguarding procedures and practice can make parents feel excluded, overlooked and even blamed (Scott and McNeish, 2017).

Reflection pointers

- As service leaders and practitioners, how do we talk about power? Are we sufficiently aware of our power and how it affects others?

- Do we have a shared understanding of where power rests in the ecology of CSE?

- How are practitioners supported to reflect on the notion of power in their practice with children who have been or are being exploited and their families?

Sex and gender roles

Connected to notions of power, the issue of gender is also important. Indeed, the power imbalance that occurs through sex inequality is particularly pernicious because of the long human history and culture of women and girls being oppressed and controlled because of their sex under the guise of ‘gender roles’ (Yi, 2015). As we have already noted, boys are also exploited and women can be perpetrators, often having been victims themselves (Stevenson, 2014), so simplistic assertions around sex and gender roles are not helpful. However, an analysis of sex and gender roles offer a very significant contribution to developing practice and service responses and it is important to acknowledge that CSE is, unarguably, linked to male violence against females.

The ways in which women and girls experience greater inequality, hardship and harm than their male counterparts are myriad. It is outside the remit of this scope to explore the wider cumulative disadvantages that women face across the life course (for a comprehensive review of women and girls at risk, see McNeish and Scott, 2014) but it is worth noting that the heightened risk of violence and abuse facing women is in the context of lifetime inequalities. Domestic abuse research illustrates the high prevalence of sex-based oppression and violence, with one in four women in the UK experiencing partner-perpetrated physical violence (Guy et al, 2014). As Williams and Watson (2016) note, the physical and sexual abuse of women and girls are widespread phenomena and can be seen as a way of establishing and sustaining male dominance – both within the family and community – or maintaining masculine identity (WHO, 2013). Accordingly, it is within the most male-dominated families, sub-cultures and coercive contexts – including trafficking and gangs – that some of the most severe abuse of girls and women occurs (McNeish and Scott, 2014). Research carried out for the NSPCC in 2009 found that one in three 13 to 17-year-old girls in an intimate relationship had experienced some form of sexual violence from a partner (Barter et al, 2009), while a later analysis of data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey found one in 25 of the UK population (80 per cent of whom were women) had suffered ‘extensive physical and sexual violence, with an abuse history extending back to childhood’ (NatCen, 2014: 1). The prevalence of intimate partner violence in young people’s relationships varies depending on the type of abuse and the definitions used, according to Barter’s review of recent studies (Research in Practice, 2016a). Clearly the scale of violence towards females is vast, and CSE connects to sex-based oppression and violence both materially and conceptually.

Some years ago, Kelly et al (1995) argued the increased awareness around sexual exploitation that has now emerged is, in part, the outcome of a strong feminist movement (alongside other influences – see Finkelhor, 1979, and Kelly, 1988). They further argued that the ‘knowledge explosion’ seen during recent decades reveal significant insights:

- that males are the vast majority sexual abusers of children

- that children are most likely to be abused by a male that they know

- that abuse takes a range of forms, occurs in varying contexts, and within a diversity of relationships

- that individuals and agencies have frequently failed to respond appropriately to cases of sexual abuse, often blaming the victim and excusing the offender

- that these findings are echoed in the knowledge developed over the last 20 years [i.e. 1975-1995] about male abuse of women.

(Kelly et al, 1995: 10)

The way in which victims of CSE are perceived and treated by services is also affected by an understanding (or lack of understanding) of sex inequality. The link between abuse and mental health problems in women has been documented over many years (Chen et al, 2010) and there are lessons from research in this field that may be useful in relation to CSE. Williams and Watson (2016) highlight the risk that a woman’s response to harmful experiences – borne out of structural inequality – may be pathologised. In expressing her distress, a woman is perceived as overreacting, hyper-emotional or hysterical (Cretser et al, 1982, note historical mental health practice in which women were sectioned and imprisoned for showing emotional distress) and so the service response can be to medicalise, diagnose and situate the problem within the woman.

A contemporary example of this phenomenon comes from medicine. Studies have found that women in A&E departments waited longer, were given fewer painkillers and were deprioritised compared to men expressing the same levels of pain (Hoffmann and Tarzian, 2001; Chen et al, 2008). The analysis of these findings includes the suggestion that medical professionals are affected by sexist stereotypes and see women as hyper-emotional and more irrational than men, and more often perceive women’s physical pain and illnesses as psychological issues (in comparison to those of men). The lived experience of pain and trauma in females is thereby downplayed, as are the inequalities underlying their experience (Williams and Keating, 2002, cited in Williams and Watson, 2016). Females experiencing abuse express their distress in many ways, some of which may be construed as problematic to professionals but may in fact be a form of resilience or survival tactics. By focusing on the expression of pain rather than the harm and inequalities that enabled it, and by comparing this with what women and girls who conform to gender role do, there is a risk not only of failing to address the issue, but of locating fault within the victim also.

The powerful connections between a woman’s distress and her lived experience are severed and without these understandings, her rightful distress and associated struggles to survive are easily misunderstood as abnormal, dysfunctional, unhealthy, out of control or dangerous. It becomes easy to assume that there is something fundamentally wrong with her, rather than that something has gone badly wrong with her life.

(Williams and Watson, 2016)

If we reflect on how young women experiencing CSE can sometimes be treated by services – for example, being described as ‘wild’ or ‘out of control’ or placed in secure settings, which may be experienced as punitive and can be counter-productive (Creegan et al, 2005) – then sobering parallels can be drawn with the picture described above. It is vital, therefore, that practitioners, service leaders and policymakers recognise and respond to the ways in which sex inequality both precipitates sexual exploitation and can lead to discriminatory approaches in the very services aiming to address its impact.

Reflection pointers

- Is an understanding of sex inequality evident in our local strategy, service response and practice?

- What measures do we have in place to ensure that everyone working to address CSE is able to recognise and understand the central role of sex inequality and discrimination? Is there more we can do?

- What are we doing to ensure that our efforts to tackle CSE are effectively connected to other local activity that seeks to address violence towards women and girls more generally?

Pornography and hypersexualisation

Reflecting on sex-based oppression leads us to a discussion about pornography and the hypersexualisation, objectification and dementalisation of women and girls. Williams and Watson (2016) note that pornography has been linked to rape, domestic violence, the sexual abuse of children, sexual harassment and economic abuse. It is worth briefly considering the different perspectives around pornography and the hypersexualisation of children.

A significant proportion of children and young people are exposed to pornography (both online and offline), which can lead to an unhealthy attitude to sex and relationships (Chase and Statham, 2005; Horvath et al, 2013). Advances in mobile technology mean children and young people are able to access far more easily than was possible for previous generations; material that is considered highly inappropriate and even damaging. A study by Martellozzo et al (2016) found that 28 per cent of 11 and 12-year-olds had watched pornography and that girls and boys reported being asked to replicate sex acts they saw in porn, with one boy saying ‘My friend has started copying stuff he sees in porn with his girlfriend, nothing major, just a few slaps here and there’ (p38). Boys have also been found to be ‘collecting’ nude images of girls after asking them to write the boy’s name on their genitals or breasts with marker pens to prove ‘ownership’ (Ringrose et al, 2013). Other researchers have also found people to be developing sexual performance and intimacy issues in their adults lives due to addictions to porn and changes in the way the brain is aroused by visual imagery rather than physical stimulation (Zoldbrod, 2013; Park et al, 2016). It is also worth mentioning that pornography itself is exploitative in nature (especially for females) and therefore children and young people need open and frank discussions about the type of sex and the context of sex within pornography. Research for the Department for Education in 2011 13 found that nine out of ten parents felt their children were being ‘forced to grow up too quickly’ and to engage in ‘sexualised life’ before ready to do so. This is thought by some to be precipitated by a celebrity-driven culture as well as increasingly sexualised media programming and clothing (see Bailey, 2011), but it is important to be cautious about suggestions of simple causal or mono-directional relationships precipitating CSE. What is vital is always to maintain absolute clarity that children deserve protection, irrespective of how innocent and chaste they may or may not present – and that the problem is how children are sexualised and how this cultural sexualisation can present new opportunities for child sex offenders that may not have existed years ago. An example of this could be that talking to a child about sex, or attempting to sexualise a child during the grooming process, may be easier for child sex offenders in the current culture of hypersexualisation of children. Children are now absorbing sexualised images and messages from an early age. In 2007 an American Psychological Association taskforce found that girls begin to self-objectify and to ‘self-sexualise’ (the act of judging oneself by sexual worth and imagining oneself through the male gaze) by the age of seven. Therefore, a sex offender initiating a conversation about sex or calling a child ‘sexy’ may not be such a difficult task now as it was when discussing sex was considered taboo.

The Children and Social Work Act 2017 requires the Secretary of State to make regulations that will require ‘relationships and sex education’ (RSE) 14 to be taught in all secondary schools and relationships education (as part of PSHE – personal, social, health and economic education) to be taught in all primary schools 15.This was a widely supported and progressive move by the government, backed by children and young people themselves. (A survey of 16 to 24-year-olds carried out by the Terrence Higgins Trust in 2016 found that 99 per cent thought RSE should be mandatory in all schools; one in seven respondents said they had not received any RSE education at all.) In this context, it is important to state that RSE does not precipitate the early sexualisation or sexual activity of children (Kirby et al, 2007; Kohler et al, 2008), despite concerns that this may be so. Effective RSE can help children and young people to manage how the media seek to sexualise them and can help them promote their own agency.

However, whilst RSE is often presented as a protective factor for children and young people in the context of abuse and exploitation (Wurtele and Miller-Perrin, 1992; Rekart, 2005; Wolak et al, 2008; PACE, 2013), the evidence base is not yet mature enough to support this assertion. Bovarnick and Scott (2016) conducted a rapid evidence assessment, which focused on the effectiveness of ‘preventative education’. They were able to identify only a limited number of studies and found extremely small or zero impact of this type of input on the sexual and relationship behaviours of children. There may be evidence of temporarily increased knowledge of the topics being taught, but it would not yet be accurate or ethical to assert that education is ‘preventative’ or ‘protective’ against CSE. That said, whilst it is important that RSE or even CSE information is not labelled as a ‘preventative education’ (as it cannot prevent an abuser acting), there are clear reasons why children should have access to early, comprehensive and modern education about relationships, sexuality and health. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out in a number of its articles that children have a right to information and education about their own health and wellbeing. Furthermore, education may help to support children and young people to recognise their experiences as abusive and so may support disclosure; although the evidence base for this is very limited at present (Bovarnick and Scott, 2016). Barnardo’s has begun working alongside young people to identify what effective prevention work may look like focusing on disrupting the development of sexually abusive behaviours and supporting the development of safer environment where abusive behaviours are identified and effectively addressed, in response to the limited evidence base discussed above 16.

Notions that young people in contemporary society are more sexually active than previous generations, and at an earlier age, are often portrayed in the media as a source of concern. A positive interpretation of this may be that young people today have access to more family planning options than previous generations and have greater sex equality, which by implication means more freedoms and thus gives them choice regarding sexual behaviour (Lemos, 2009). On the other hand, a feminist perspective argues that pressure to be sexual at a younger age is actually evidence of sex inequality and results in fewer freedoms not more, especially in light of societal pressures and sexual culture (Attwood, 2006; Coy, 2008; Kelly et al, 1995).

We need to acknowledge that tensions do exist between liberty and safety. For some young people, early liberation and the desire for increased independence, coupled with (healthy and expected) reduced parental supervision, may present an opportunity for a child sex offender in their environment to target them (Ericson and Doyle, 2005; Barnardo’s, 2011a). Therefore, culturally expected developments during adolescence – such as reduced parental supervision, meeting new people, visiting new places, starting to date and starting to explore sexuality – can often be presented as ‘risks’ or ‘vulnerabilities’ to CSE, which can inadvertently problematise normal developmental changes and experiences. More recently this has led to these normal developments and positive risks sometimes being negatively reframed as ‘risk taking behaviours’ that need to be ‘reduced’ by professionals.

Key messages

- Practitioners and local policymakers need to be attuned to the availability and impact of pornography, and to provide young people with effective counter-narratives of sexuality and to discuss the exploitative truths of pornography as an industry.

- Liberty does not exacerbate risk per se. Supporting age-appropriate, positive risk is an important part of healthy child development.

- It is important that positive risks, decisions and developmentally appropriate changes are not framed as problematic or pathological in nature when considering the possibility of CSE.

- Children and young people should be afforded protection and allowed autonomy, even if they are a CSE victim themselves.

Getting the balance right is important.

Reflection pointers

- How are practitioners supported to develop their confidence and ‘literacy’ with regard to developments in social media and new technology?

- How do practitioners and services beyond those focused on CSE, including schools and youth services, challenge unhealthy sexual narratives?

- How are parents, carers and young people supported to understand adolescent development, and the associated challenge of balancing liberty and risk?

'Risky behaviour', 'choice' and other euphemisms: Victim blaming in CSE

When working with young people, the response of practitioners may reflect faulty assumptions that adolescents and other young people are more resilient than younger children by virtue of their age, despite having experienced more cumulative harm (Rees and Stein, 1999; Stanley, 2011). And as already discussed, professionals can inadvertently compound such misconceptions through their attitudes and language. Describing victims as ‘risk taking’, for example, locates responsibility in the victim; describing perpetrators as ‘lads’ (Bedford, 2015) underplays threat. The use of euphemisms and ambivalent language can allow risk to go unseen. For example, professionals might describe a 12-year-old girl as ‘sexually active’ or a 35-year-old male as a 14-year-old’s ‘boyfriend’ as opposed to an abuser (Beckett, 2011b).

As noted in numerous serious case reviews (SCRs) and inquiries, CSE is sometimes not acknowledged because the young person is seen to have engaged in ‘risky behaviour’ and/or made risky ‘choices’; therefore responsibility has been placed, implicitly or explicitly, with the young person themselves. Confusion exists around age and consent in relation to CSE; sometimes, children and young people are seen as having ‘consented’ to their own exploitation. As the Local Government Association states:

Pearce discusses this issue, noting how instead of being viewed as victims of abuse, young people (particularly those aged 16 to 18) who were being sexually exploited ‘were invariably perceived to be consenting active agents making choices, albeit constrained, about their relationships’ (Pearce, 2014: 163). This resulted in them being apportioned blame and a degree of responsibility for outcomes which diverted attention from their vulnerability and from the actions of the sex offender. When we consider this misconception against the wider backdrop of worrying attitudes towards women’s sexual safety – according to a 2009 Home Office poll (see EVAW, 2011: 5), over a third of people believe a woman is wholly or partly responsible for being sexually assaulted or raped if she was drunk, and over a quarter think so if she was in public wearing sexy or revealing clothes – then it is clear that young female victims are at heightened risk of being held responsible for their abuse.

Another complication for older teenagers may arise in relation to the recent revision of the cross-government definition of domestic abuse to include young people aged 16 and 17. Although valuable in highlighting domestic abuse among older teenagers, the definition has the potential to further obfuscate cases of CSE. For example, Pona et al (2015) relate the case study of a 17-year-old girl with an abusive boyfriend who is also sexually exploiting her. Because of her age, the girl is judged by social workers to be experiencing domestic abuse rather than CSE, a judgment that does not capture all her particular vulnerabilities and makes it more difficult to protect her. It is important to acknowledge that domestic abuse and CSE may both be present and indeed overlapping, and may require different yet connected safeguarding strategies.

Overplaying the extent to which young people are exercising informed rational ‘choices’ is a theme that emerges in many CSE-related SCRs. What can be interpreted as ‘risky lifestyle choices’ may more accurately and more helpfully be understood as (mal)adaptations to earlier trauma, or as attempts to meet unmet needs (Hanson and Holmes, 2014). For example, a young person may have low self- regard and feel worthless, and may crave love and affection. A sex offender may therefore exploit this opportunity by showing false ‘love’ and ‘affection’ in order to abuse the young person (Elliott, 1995; Finkelhor, 1984). Or a child may have developed dissociative coping strategies when experiencing harm – for example, sexual abuse in childhood – which later inhibit their ability to identify that they are being abused (for more on ‘betrayal trauma theory’ see DePrince, 2005; DePrince et al, 2012). In addition, young people might believe (possibly set against the context of prior maltreatment or neglect) that they deserve no better than their exploitative relationship (Reid, 2011). Furthermore, the capacity to dissociate from pain or negative feelings (an adaptation to earlier trauma) can inhibit a young person’s ability to recognise their own distress. Understanding how previous experiences might (for some young people) underpin behaviours is important for practitioners, and demands a more sophisticated interpretation of 'choice'.

In order to address victim blaming, it is important to explore why people may hold these common beliefs about victims of sexual abuse. There are a number of complementary and interlinked theories that attempt to explain the social phenomenon of victim blaming and the cognitive reasoning underpinning the shift of responsibility from the sex offender towards the victim. Eaton (forthcoming) uses Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (1979) to explore in detail the wide range of empirical evidence about what contributes to victim blaming at each level of society. The main theories considered by Eaton are:

- Belief in a Just World (BJW) (Lerner, 1980) – the cognitive bias held by many people that the world is a just and fair place in which people deserve what they get and get what they deserve. Originating from religion, people believe that good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people, so if something bad happens (being sexually abused), there must have been something they did (or didn’t do) which meant they deserved the abuse. The evidence for this theory is wide ranging, global but inconsistent. Many theorists argue that BJW explains victim blaming; others contest this as oversimplified, as some studies have shown that BJW attitudes do not correlate with victim blaming attitudes. Beliefs that bad things only happen to bad people act as a self-preservation tactic, to protect the self from feelings of vulnerability. Accepting that the world is a random place in which random (sometimes terrible) things happen to individuals for no reason at all, can create anxiety and uncertainty in humans looking for reason and balance in the universe (Eaton, forthcoming).

- Rape myth acceptance – a collection of harmful myths and stereotypes about victims, offenders and offences which affect how the victim is perceived. Rape myths include the expectation that the victim would report immediately, would have obvious physical injuries, would not know their attacker, would adequately fight off their attacker and would want to pursue prosecution (McMahon and Farmer, 2011). Rape myth acceptance attitudes are held by between one third and half of the population 18. When rape myths coalesce they form the notion of ‘classic rape’, which is what the public and professionals are commonly used to seeing and hearing about in the media, and the ‘infallible victim’ stereotype which describes the ‘perfectly innocent victim’. When a child or adult discloses sexual abuse or assaults that do not conform to the classic rape stereotype, they are much less likely to be believed, and are more likely to be blamed for their abuse or assault (Eaton, forthcoming).

- Individualism and self-preservation theories (Burge, 1986) – ‘individualism’ refers to an ego-centric, individualistic culture in which children and adults are taught they are responsible for their own lives, behaviours, actions and consequences. This may contribute to victim blaming and has been found to contribute to the use of the word ‘responsible’ and ‘irresponsibility’ in relation to young rape and sexual assault victims in college and university settings, with students arguing that victims are ultimately responsible for keeping themselves safe and avoiding sexual attacks (Anderson, 2001). This has links to self-preservation theories in which people create distance between themselves and victims by finding differences in their behaviours or characteristics, thereby reassuring themselves that they would never be a victim of sexual violence because they wouldn’t make those same mistakes (e.g., ‘Well, I never hang around in parks so that would never happen to me’ or ‘My family and I live in a nice area so our children will never be exploited’). The impact of victim blaming is significantly correlated with future revictimisation, self-blame and mental health difficulties (Filipas and Ullman, 2006; Miller et al, 2007). For a more detailed discussion of the theoretical frameworks and socio-cultural factors surrounding victim blaming, see Eaton (forthcoming).

In CSE specifically, it is of paramount importance that children are viewed, protected and supported as victims of serious crime and not as culpable, deserving or at fault in any way. Changing the language that is commonly used – such as ‘risk-taking behaviours’, ‘vulnerabilities that lead to children being abused’, ‘promiscuous behaviours’ and ‘unhealthy choices’ – is a vital step towards reducing victim blaming of children affected by CSE. This should be accompanied by comprehensive training and information for professionals on the origins of stereotypes, biases and victim blaming narratives.

Reflection pointers

- How is choice discussed, described and understood by practitioners across services for young people at risk? Do our practice norms or service responses inadvertently imply that blame or responsibility sits with the victim?

- What steps are we taking to ensure local services and approaches do not inadvertently label young people? Is there more we could do?

Key messages

- Service leaders and practitioners need to have a strong understanding of the role played by power and inequality, and sex in particular, in relation to CSE. Practitioners need to be alert to these issues and consider the power they themselves hold in their relationships with families.

- Practitioners must recognise and challenge negative and unhealthy attitudes towards sexual activity, sexuality and gender roles, and not work simply to address behaviours. Practitioners must be alert to the influence of pornography, for example.

- Although they may sometimes appear to be making an informed choice, young people cannot and do not ‘choose’ abuse or exploitation. Recognising the underlying factors that can exacerbate risk will help practitioners understand and interpret apparent ‘choices’ and avoid the danger of apportioning blame.

- It is important to understand how earlier trauma might play a part in compounding risk for CSE. However, evidence must be applied critically to avoid reductionist or simplistic interpretations.

- Sex offenders can target 16 and 17-year-olds, not just younger children. Even when young people become young adults, they still have a right to be protected.

- There are a number of theories that may explain why children are blamed for being sexually exploited. Professionals should be supported to understand overt and covert victim blaming.

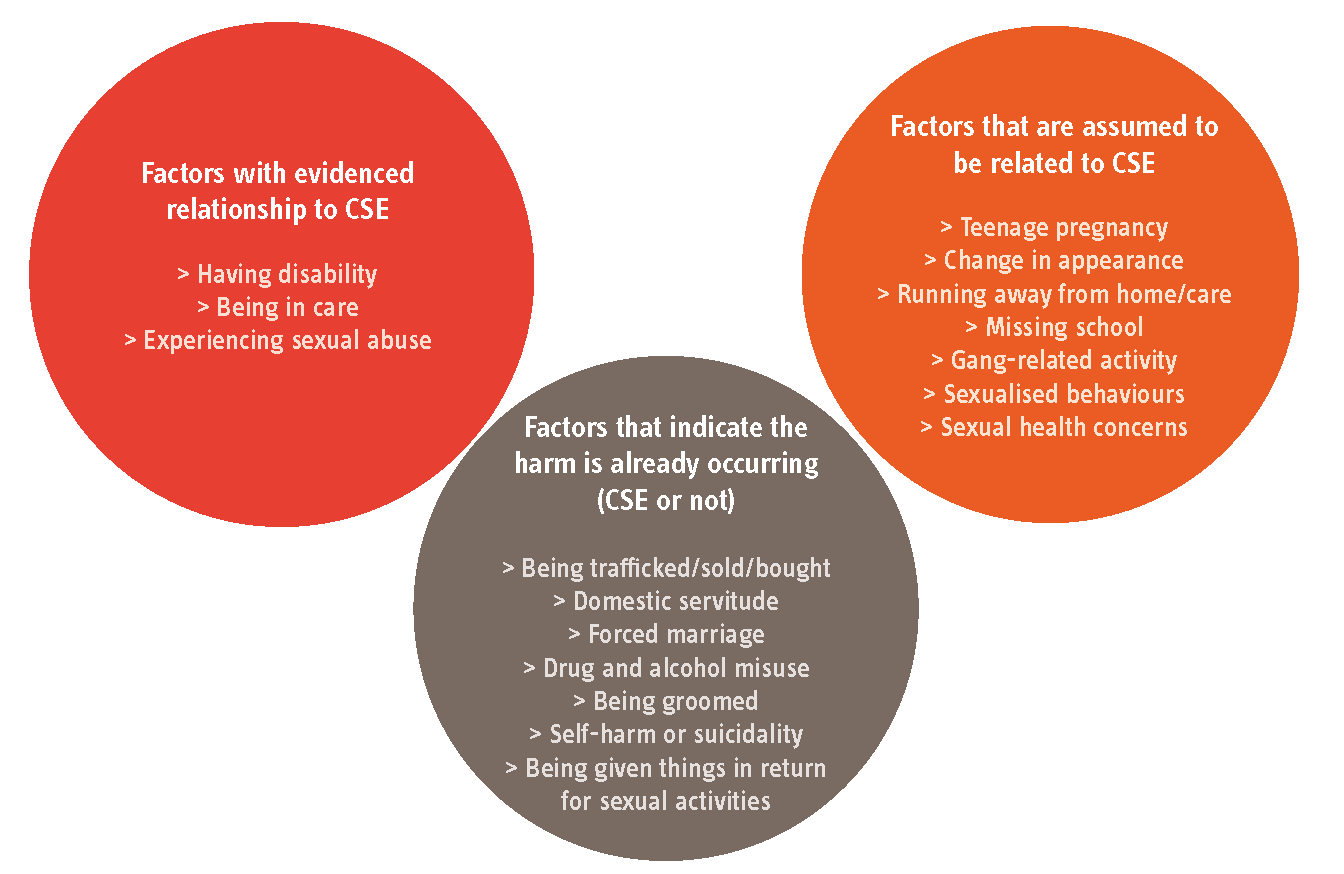

3. Vulnerability, risk and ‘models’ of CSE