There is one thing we know most definitely about care, protection and support with children, young people and families – that trusting relationships matter. The most striking work in our sector creates conditions in which relationships of trust can be made and maintained – in partnership with families, within families over time, up and down professional hierarchies, between public servants and communities, across local safeguarding partnerships.

Of course it doesn’t then follow that relationships in and of themselves are sufficient basis on which to allocate resources. In fact, we can see how badly trust is damaged when procurement activity lacks transparency and the available evidence suggests that public resources are allocated on the basis of pre-existing relationships between supplier and commissioner.

The Care Review’ activities, processes and structures will need explicit attention to these questions of trust and transparency. If it is to achieve its aim of reforming systems and services the Review will need to engage expertise of sector leaders, learn from research and from previous reviews, reflect critically on the impact of national policy decisions, austerity and the pandemic and the voices of experts by experience. There is time to build an inclusive and participatory Review and this blog offers consideration of why and how the Review might to be developed in an evidence-informed way.

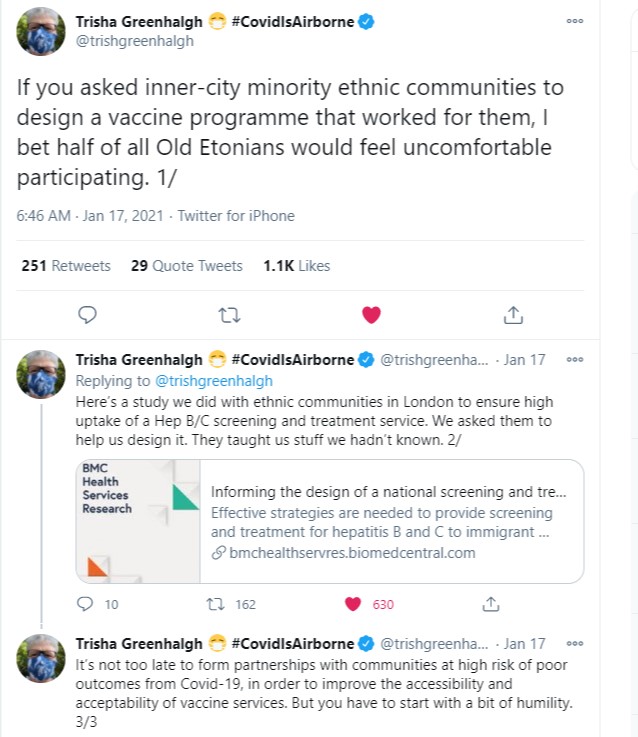

‘Start with a bit of humility’

As Trish Greenhalgh’s work in general, and these recent tweets underline, if we want citizens to be involved with any public service initiative, we need to ask them to be part of designing it and let them ‘teach us stuff we hadn’t known’. An experts by experience group is a good start, but we need to go further than that.

In efforts to engage experts by experience, we must acknowledge that for many who’ve had social workers involved in their lives or have been in care, trust in a relationship with the state has been impeded or damaged by those experiences. We must draw on what we know about trauma-informed practice to create as safe and supported an environment as possible within which experiences and views can be shared. The Truth Project and the support they offer people sharing their experiences with the Independent inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse provides a strong example of what can be done.

Recognise the role of research

Clearly the expertise of those with lived experience is vital to making this Review a success. We must also recognise the important role that other forms of knowledge have to play. Whilst social care is a field with fewer randomised control studies than, say, health, our sector benefits from a rigorous, rich, mixed methods research, though there is a significant dearth of longitudinal studies.

To explore the system conditions, trends and policy angles relevant to this review, it will be important to use analyses of large scale data sets to reflect on the workings of Children’s Social Care in context. In doing so we must keep alert to the knowledge that that unique stories underpin every statistic. If we isolate our focus to individuated data items that are countable we risk losing sight of what counts.

The most pervasive context for the work of Children’s Social Care – as shown by the Child Welfare Inequalities Project (CWIP) – is family and neighbourhood poverty and deprivation. The Review must start with explicit recognition of this. We cannot continue with the deep, structural problem of poverty hidden in plain sight, the ‘wallpaper of practice: too big to tackle and too familiar to notice’ (Morris et al, 2018:18). Like CWIP, the best of our research evidence brings data analysis together with qualitative research and foregrounds the experiences of the people behind the data items with their recommendations for change.

In this sense boundaries between lived experience, research and practice are not distinct. Many of those engaged in research began their careers in practice, many in practice and/or academic roles bring lived experience. To benefit fully from these rich sources of knowledge the Review will need to design processes that triangulate and integrate them, rather than conceptualise them as separate or – worse – in conflict with each other.

Be brave and balanced

This review will involve hearing difficult messages – albeit that these messages are unlikely to be new. It will be uncomfortable – painful indeed – to confront the failings of our system.

As Ian Dickson points out the majority of young adults leaving care ‘are absorbed into the wider community notwithstanding the extra challenges they face’. It’s also true that far too many experience the multiple challenges, which we see reflected in statistics on education, employment, mental ill health, homelessness, incarceration.

Perhaps the ultimate indictment of our ‘corporate parenting’ is that 40% of the mothers returning to court to experience loss of another child in care proceedings spent time in care themselves. Many are teenagers, the largest proportion entered care aged ten years or older and half experienced multiple placement moves. As ‘corporate grandparents’ we can and must do better than this.

There is ground-breaking work going on in a diverse community of small, local services working with parents who’ve lost children into care as well as through national initiative and we must bring the learning from all of this work to the Review. Evaluation shows that trauma-informed, relationship-based work with birth parents can build trust, facilitate advocacy and real change – both practically (with housing and debt management), and therapeutically (in terms of self-worth and improved relationships with children no longer in their care).

This Review has a balance to strike. Like a skilled practitioner, it will need to be unflinching in acknowledging concerns, whilst also recognising the conditions that lead to these concerns and identifying and amplifying the strengths where they exist.

Be inclusive

The Experts by Experience group will play a vital role in this Review. However, to ensure diverse and inclusive representation, every effort must be made to create multiple mechanisms for influencing and informing.

Voices from this large and varied population are better heard now than at any time in the past via social media and a rich range of groups and organisations. Some, such as @Careexpconf and @OurCareOurSay2 have done essential groundwork for this Review.

Given that around seven in every 1,000 UK children are currently experiencing the care system and around 10,000 young people will leave care this year. We might extrapolate that there are around half a million care-experienced people in our communities. Alongside those are their parents, brothers and sisters, grandparents.

In 2021 we have unprecedented opportunities for involving children in care, care-experienced adults and their families through online platforms, social media and family and care-experienced groups and organisations. It will be important to reach out widely and swiftly, perhaps in a series of targeted, online citizen’s assemblies and thereby draw on a range of voices to shape the aims of the Review.

Let’s commit to making sure that this ‘once in a generation’ opportunity begins from a place of recognition that families’ experiences with Children’s Social Care are intergenerational and relational and take place in demographic context.

End note: Research in Practice will collate a range of materials we have published that might inform the Review, and will make these publicly available.